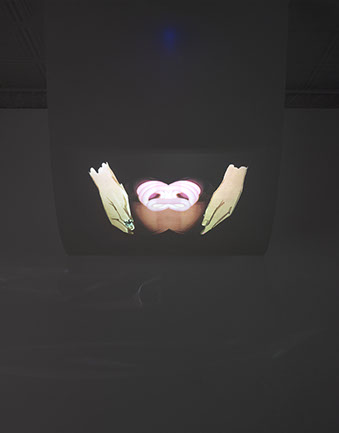

Diaphragm (Let Me Hold Your Breath), 2017

Video projection, plastic, dimensions variable

Photograph courtesy of Tal Barel

Ada Potter with Tal and Liz

I first met Tal Gilboa and Elizabeth Stehl Kleberg while in graduate school. At the time they were in the early stages of their collaboration. Their work stood out immediately for its deeply beautiful, sensitive approach to materials and space. Their exhibition Let Me Hold Your Breath curated by Zachary Lucero is up until December 16th at Baxter Street Camera Club of New York

Ada Potter: One thing that struck me is that your pieces are not that long. I think the longest was roughly four minutes, and they’re all playing on a loop. Honestly, video work can be challenging because I feel like I’m not always able to sit down and commit to watching an entire piece. It's also immersive, so you immediately get the mood and tone. It’s not like a visitor takes a seat in a theater and has a traditional cinematic viewing experience, which I really enjoy about your work.

Elizabeth Kleberg: We often talk about the expectation for a narrative arc when you watch a video work, about the need to watch the beginning, middle, and end; there’s a point and you need to draw a conclusion about the story. Sometimes I think that’s frustrating.

Tal Gilboa: Yeah, we like to think of our videos as spatial things, and not just moving images. They become sculptures in space, and that breaks it apart from the movie theater experience. You can just take it in for a few seconds, and it could be enough if that's all you have, or you can stay and linger and hold it and take in some more.

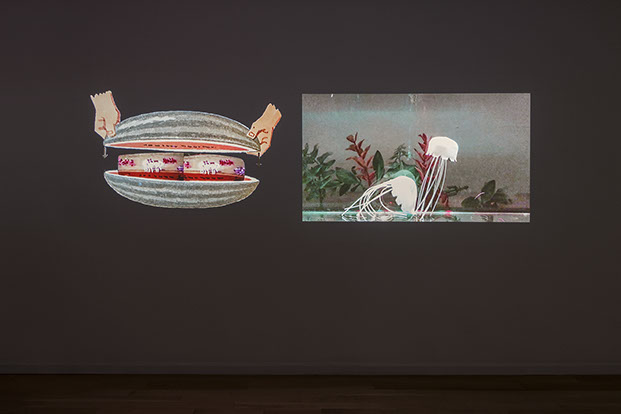

Let Me Hold Your Breath, installation at Baxter Street Camera Club of New York, 2017

Photograph courtesy of Tal Barel

AP: Speaking of space, I really enjoyed how the work Diaphragm creates a real physical feeling in the viewer. I started to feel my own breath. It reminded me of an earlier generation of sculptors like Richard Serra who were interested in inciting a bodily sensation in the viewer.

EK: I think we are always wanting to create things that have an experiential quality, but we’re weary of it being too immersive, transportive, or over the top. I mean, we love it. We loved for example, the Pipilotti Rist show at the New Museum, especially the old work. But sometimes when you’re surrounded by it, your senses can get overwhelmed by it all. And for us, there is something quirky about the installation, where you can enter and come out, and it doesn’t give you the whole experience upfront.

TG: I think that it’s not that we don’t enjoy the idea of the viewer being immersed, but there is something to our relationship that likes the idea of keeping it open-ended because we are more than one. And so having a monolithic experience is not what we aim for. We are often surprised at how minimal the sculpture ends up being, right? When you look at this show, there are five video pieces in a not-so-big space, but you can still potentially look at each one as just one thing.

AP: That makes me think of Claire Bishop’s Artificial Hells, where she’s reacting against participatory art and Relational Aesthetics. She critiques how the viewer is being told what to do, which is in some ways similar to a cinematic experience.

EK: It’s true that there can be an impulse in Relational Aesthetics, and maybe in contemporary art, to declare: here’s the point, here's the aim, here's the press release about it, so go and experience it, and you already know what to expect and what the goal is. That singular message and focus is something that we just don’t start with, because we are two people. We're just now finally articulating the fact that we have different interpretations after we finish specific works.

TG: I think the best example of this is Pink, that we both love and obviously relate to, and because it references a body you can talk about the female body representation in art and culture, but then when we try to articulate what we each think about it, for me, it's very much about lesbian relationships and lesbian sex and desire, and for Liz it's very much about...

Pink, 2017

Video projection, plastic mirror, mylar, dimensions variable

Photography courtesy of Tal Barel

EK: Motherhood.

TG: ...and breastfeeding and how her relationship to the breasts changed drastically.

EK: How they’re not my own anymore. These really powerful parts of my body right now, that I’m re-understanding, sometimes it’s a painful experience but also this really powerful new experience of my body. And so we had a moment where we realized that we can be both equally excited about a work, and it can be something different for each of us.

TG: And so it’s not either-or; it’s both at the same time. And then when a viewer, who is sometimes just scared of looking, asks what it’s about, we always just want to say, “What do you think?” not because we don't know what it's about, since we obviously do, but because we know it can be more than the one thing.

AP: This is what makes Pink so effective, it gets at all these things you're talking about, you're physically pointing to and holding a signifier of femininity. I feel like that work is more and more successful the more we talk because it gets to so much–and it's also just funny and playful and beautiful.

EK: I think the collaboration allows for a really personal voice to live alongside a collective voice, making something that is deeply personal and universal. You just have to make what feels real and potent to you. How did Zachary say it?

TG: Two voices that are more than an individual and less than a community.

AP: I have a bunch of questions about the collaboration. I think there's something political about collaboration and I wonder how you feel about that? I remember in grad school that you guys had a lot of weird hoops you had to jump through with the institution to gain recognition as a “legitimate” collaboration. But also out in the larger world, I think it’s powerful to say you’re part of a collective, especially right now.

TG: Definitely. And I think those hoops we had to jump through were very important to us. I mean, they were frustrating at the time, sure. We were asked once: “You gotta understand, we need to know, who's the horse and who's the cart?” Did they really honestly assume that one of us was doing all the work and the other one was just slacking around and we're covering for each other because we're friends? It's incredibly insensitive and insulting. To be honest, it reminded me of people asking a lesbian couple “who's the guy who's the girl?” It’s exactly the same assumption of hierarchy. On the other hand, it's totally energizing, to have something so concrete to go up against…

EK: Yes, this question ended up being a fruitful way of articulating who we are for ourselves. Assuming that there is a separation and hierarchy of responsibility, which maybe allowed them to decide which one of us is better or something - this really got on our nerves. So pushing back on that was really important for us.

AP: Yeah, so to clarify, you guys do everything together, both sets of hands are involved at every stage?

TG: Sometimes when we edit one of us is holding the mouse and the other one is holding the keyboard. We make this hybrid; one is pressing shift and the other one is clicking the mouse. When we are in a good vibe of course.

EK: Or when we have Waylon [Elizabeth’s four-month-old son] and have no hands.

AP: Do you work independently?

EK: Sometimes we start stuff independently but lately it all folds back into the collaboration.

AP: What makes your collaboration successful? Are there things that you have found that have helped you work together?

TG: One thing that we learned to articulate in school is the improvisational part of it. I think we practiced it without being able to say it, then we took the amazing Improvisation For Artists class at Pratt with Hollis Witherspoon. Before we just knew that it was very fluid, taking in whatever is suggested, but in a structured sort of way. We learned that in improv it's called “Yes, and…” and it just made so much sense. I think that this idea of trying everything, not committing or assuming anything beforehand, is at the core of our collaboration. There's no reason to say no, and if it doesn't work we'll try something else. When you just keep saying yes, you keep going, and build one thing on top of the other—they call it gift giving, I think, that makes it successful.

EK: The only times things have gone wrong we realize after the fact one of us said “no, but...” Also if we don’t listen, which is another way of saying no, it doesn’t work.

Pears, 2017

Projector, HD video, glass, wood, metal, cement, 54"x22"

Photography courtesy of Tal Barel

AP: So you're dealing with representation and the female body, and you are two women. I guess since Trump I can't help but now ask more questions about how art addresses the political. Do you guys think in those terms?

EK: I think something we’ve talked about a lot recently is that there's an expectation and an assumption that everything you're doing now is political and should be important in this new context. What does it mean if we sometimes want to make something magical? We have bashfully said that to each other. I had a low moment when I was really exhausted and we were in the studio with the baby, and all I could say is, “I just really want to make something that feels, and that I feel.” But then we stopped—can we do that? Because it doesn't initially feel urgent enough right now.

TG: First of all I think that it's been going on since before Trump. It’s really easy to say that the political climate now changed everything, but come on, we know that two women who make art together has been a radical thing since way before. Roni [Tal’s girlfriend] is writing an abstract for her dissertation now, and it’s so similar to an artist statement - you have to be able to articulate your message and explain why it's the most important work that has ever been done in the history of thinking. Her idea is so complex and nuanced and it feels as if going to a protest with a sign saying: “Give the people nuance!” I mean, how can you shout that at the top of your lungs? If what you’re motivated by is a sense of urgency there’s very little room for nuance. I think that's what we're doing, we’re saying: We Are for Delicate Moments of Connections. Can you protest for that? No, you can’t, so you make art about it.

AP: I think that sign would be amazing! I think that needs to be at the next march.

EK: There’s this common assumption that aesthetics or beauty are a cover-up for a disturbing reality. That’s why sometimes we struggle with the seduction of video, of moving image, of shiny materials. But it’s not just escapism to have beautiful ephemeral experiences. It’s knowing that this is what we need to make in this present reality. We need to feel those moments of connection. And maybe that’s what the work is about, so it's not just feminine and pretty.

AP: I agree, I feel like this is how we create institutional, structural change, by creating more moments and spaces for feeling and connecting.

TG: I just read this blog post that blew my mind by Sara Ahmed, a brilliant feminist writer. She talks there about Wonder as a feminist pedagogy. She explains how you can look at the idea of Wonder as a naive, childish encountering of the world for the first time. But if you take this force and you remove the first-time-ness of it, you can use it as a tool to investigate the world, to keep on questioning your reality, to challenge it over and over again. And if you take this idea of Wonder as a tool and put it in our context–in an art context–it keeps you going and keeps you wanting to understand the world, and to expose it for what it is and not just accept it as is. Wonder can be really powerfully moving. You look at something, and you’re shaken, and then you're moved into action. It’s vital and gives you energy to not accept the status quo. It gets you to look at the material aspect of the world, at power structures for example, and question all these things that you can blissfully not notice if you want. But if you are able to approach these struggles through Wonder then it's not as discouraging.

AP: What is a studio day like for you guys?

EK: It's a very weird thing to have a self-directed studio practice. Especially compared to Matt [Kleberg, Elizabeth’s husband], who is a painter. For him the parameters are very clear. When we come in we really improvise. It always looks different and it’s very playful.

TG: It's like seriously playful or rigorously playful; not committing to one thing. It’s very fast paced and we move around from a collage to a video to bending a piece of plastic. The starting point is usually a video or a cut image on paper or even just a shape. For example, I'm into arches right now, or I’ve been thinking about columns, or it's about the feeling of hands holding something. Liz has been saying that this is the shape of this show, hands gently holding something that can’t be held.

AP: I was wondering what the source of the dance video is in your two channel piece, This Shape Has No Place?

EK: All of the dance clips are from one piece of archival footage of Rudolf Laban class. His technique was based on shapes and geometry, also incorporating everyday movements. So in some videos there's a group of people doing the same motion like ringing out something, or stirring something, moving a chair back and forth–almost in an improv way, usually collective movements. I was using a lot of Martha Graham technique videos before because my mom was a modern dancer and she studied the Graham technique. But Martha Graham is very narrative and rigid, but beautiful too. This Laban technique has a structure, but is looser. The idea of choreography is something we talk about; the choreography of working together and the choreography of the materials and videos in space. I started working with dance from my personal connection and it came back around to the collaboration in a very fitting way. We have some books about dance from my mom from college and they are very visual in the way they show how choreography is built by drawing shapes in space.

This shape Has No Place, 2017

Two channel video projection, 4:54 minute loop

Photography courtesy of Tal Barel

AP: The jellyfish footage was so funny to me. It takes a minute to realize it’s fake and it feels like it can be in a restaurant or a dollar store. It’s like a weird simulacra of something. They're not sentient beings. They're not moving on their own accord, but you're watching this thing that feels so full of emotion. Did you guys compose the music for the piece?

EK: Yes. When we used sound in a previous piece, Whale, we got a friend who is a composer to compose the sound for that. For this piece we wanted to work with sound again. We composed it using some found sounds and our own recordings on Garage Band. I think I was more hesitant to put sound into this show; because it can be so powerful I think it needs to have the right weight to it.

AP: So the digital elements of your process, do you treat that differently? Do you think of it differently conceptually working with digital material?

TG: We make videos and we use our iPhones, so it’s a little inevitable. I do think that we like it when it's not just high-tech, super sophisticated computer programed projections. We like when there's a high-tech/low-tech balance with the materials in the space. So you have the projector, but you also have a physical object like a piece of plastic or a sheet of paper.

EK: Editing to us feels a lot like drawing and collage-making. We've resisted the super high-tech, slick, awe factor. We like it when the projection meets material and they have to negotiate and compromise into a hybrid thing. It’s the unexpected and uncontrollable moments when the manipulated video meets an object - the image breaks, reflects, expands - these are the moments of Wonder and surprise that we look for.

This shape Has No Place, 2017

Two channel video projection, 4:54 minute loop

Photography courtesy of Tal Barel

AP: I noticed there was some pixelation that felt very intentional.

TG: We really like Hito Steyerl’s writing on contemporary images. She helps us think about the pixelation as the material of a digital image. When something is copied again and again it gains qualities of history and space. It ages.

AP: Yeah, and it's nice to see that right? And lay it bare rather than try to wash it away and make it pristine again or true to some thought of an original...

EK: Right. The found footage, iphone videos, and the videos we shoot in the studio–we use them all as equal materials.

TG: We like the idea of gleaning images from the world. We took this from a Laura Mulvey essay. It got us thinking about gleaning and collage-making as a feminist act of taking what's left behind, putting that in the center of things and transforming this center/fringe relationship.

EK: Collage is what connected us in the first place and is still a strategy for how we come together and make work.

AP: Before we finish, how did you guys get hooked up with Baxter St [The Camera Club of New York]?

TG: It was through an open call for curators.

AP: So Zachary submitted the proposal?

TG: Yes, Zachary Lucero wrote the proposal with us. He is such a beautiful writer. It was great working with him.

EK: Zachary has been to stuff at the Camera Club because he is a photographer and a poet, and they do poetry nights too. They are really cool. I feel like they have lots of artist-oriented programs and are really supportive. They helped fund the show and the curator gets a stipend as well. We were able to buy projectors and materials, which was huge for us.

AP: You also have an upcoming show in Israel?

TG: Yes, in the summer, at a really great Gallery in Jerusalem called Barbur. It’s an artist-run gallery and they've been doing amazing shows lately. So we are excited about it.

EK: Yeah, and I’ve never been, so it will be my first time.

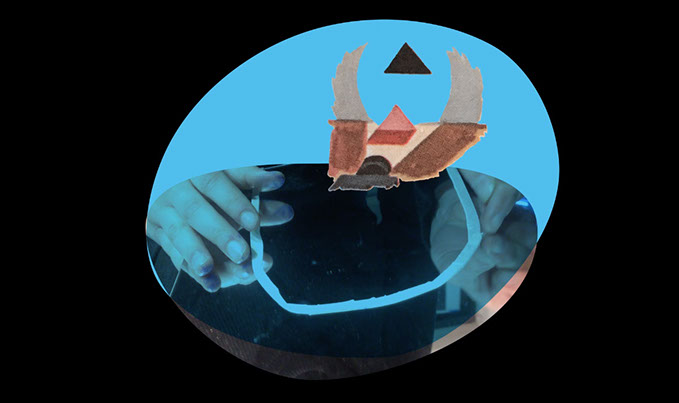

Emblem, 2017

HD video, 1:14 minute loop

Photography courtesy of Tal Barel

Tal Gilboa (from Jerusalem, Israel) and Elizabeth Stehl Kleberg (from Virginia, USA) are working together in Brooklyn. It is a collaboration between two artists and collected footage; the artists meet each other as their materials do - through dialogue and improvisation. They received their MFAs from Pratt Institute in 2016. Their work has been included in solo and group shows in New York at SOHO20 Gallery (NY) The Boiler Room, Pierogi Gallery (NY), Mulherin New York, Taylor University (IN), and Wayfarers Gallery (NY). In 2016, they were finalists for the Rema Hort Foundation Emerging Artist Grant. They recently completed a residency at Vermont Studio Center and solo exhibition at Baxter St. Camera Club of New York (NY).

Let Me Hold Your Breath

Exhibition dates: November 2 – December 16, 2017

BAXTER ST

The Camera Club of New York

126 Baxter Street

New York, NY 10013

Gallery Hours: Tues-Sat from noon-6pm

Ada Potter is an artist and curator living in New York. She has an MFA in Sculpture from Pratt Institute and a BA in Art History & Studio Art from Barnard College. She has participated in exhibitions at 20|20 Gallery at the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts, ArtHelix, A.I.R Gallery, The Boiler, and the Bruce High Quality Foundation. She curated a group exhibition entitled Future Touch at Hionas Gallery in 2016 and is the founder of SCREEN_, a email-based art "space" that produces monthly artworks, sent/received via email. Her work re-stages products such as screens and webcams; making these forms tangible by printing them on organza, mylar and acetate. Her objects seek to perform a multiplicity of material realities that underlie the anxieties that surround technology.

Disclaimer: All views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors, owner, advertisers, other writers or anyone else associated with PAINTING IS DEAD.