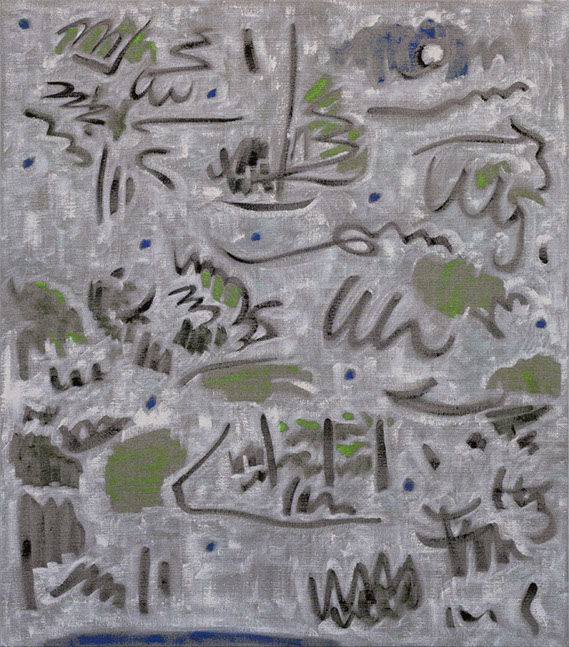

Grotto, 2016

oil on linen, 16" x 20"

photograph Scott Robinson

Scott Robinson with Ryan Nord Kitchen

SR: So how did your work develop? What’s been your trajectory?

RK: It’s always been drawing, ever since I was little. It was never too focused–up through maybe even college, I was just copying things, never taking things too seriously, never defining myself as an artist. My parents started me in piano lessons when I was seven, and I began studying music, particularly percussion. I was actually doing that for a while through college, but switched focus to painting halfway through. So I feel like the rhythms I picked up carry over into the work. It was more apparent in my previous body of work–more literally exploring overlapping dissonances and harmonies through pattern and repetition. But after a while, it just felt a little dry. So I started bringing in more of the more nameable landscape forms and letting them get a little bit more figurative. Partly, that’s because it was more engaging. It felt better to begin work with autobiographical material and let it dictate at least some of what the content was. I’m not interested in making work about myself, but I do think it’s more relatable to paint from real experiences.

SR: What kinds of real experiences do you tend to paint from? And is there a specific example you could talk about?

RK: Yeah they all start with a recollection of a place I’ve experienced. Sometimes I’ll draw from multiple perspectives of the same location or combine a few different memories into the same composition. My partner and I are always looking for new gardens or places to explore. Many of the paintings can be traced back to locations along the east coast, while some go back to memories I have from my childhood in Minnesota. Chanticleer Garden– west of Philadelphia–was the impetus for the four pieces I showed at Rod Barton last January. It was also in a few of the pieces I showed at Nicelle Beauchene last Spring.

SR: How much does what you read or watch influence what you’re doing in the studio?

RK: I think personal life is always going to seep in. You can’t avoid it. In the past I’d watch a lot film, just looking really–especially with foreign films when the language barrier keeps you disconnected a bit. The flow of Peirrot le Fou, for example. I also got really into Kurosawa when I was younger. The locations in Rashomon are so beautiful. I love the scenes where the trees themselves would appear still, but the shadows cast by them would be moving, or vice versa. Since my studio practice involves a bit of quasi-automatic drawing, I think the images and feelings I’ve experienced all work their way in.

Fish Pond, 2015

oil on linen, 12" x 15"

photograph courtesy of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery

SR: I know community is important for artists. Where did you start out?

RK: I started out in Minnesota, I grew up there, and then moved to Baltimore for grad school, and then I came up here to Brooklyn.

SR: How did you feel coming out of grad school. Lots of artists I know came out weren’t quite sure how to process what they’d just gone through.

RK: It’s still pretty fresh, only a few years ago. School was a lot of criticism. If anything, I spend less time now trying to explain to myself what I’m doing, and just work. Always trying to rationalize, explain it to my peers during school kept the work really stiff in hindsight.

SR: I think that happens for a lot of people, where they shut down in one way or another for a year or more. Sometimes they can’t even work for a while. What you’re saying reminds me of Fairfield Porter and Milton Avery, the way they worked, responding to their environment.

RK: Yeah lately it’s been helpful to keep the intellectual side of it at an arm’s length. Not to say that I don’t appreciate that aspect of painting, but it’s easy to lose myself in it.

SR: What’s an example of something that might hang you up? How would you lose yourself?

RK: It’s daunting to think of yourself as continuing some sort of tradition in painting. Seeing even a single good show can be enough to cast doubt in my mind. What more can I possibly have to offer here? It’s easy to become overwhelmed by the weight of history. I try to keep my focus more local. What do I personally want to see more of, or what do I want to share with the people around me? After school ended the work began to come more easily. I think it was a context with less expectations.

Winter, 2015

oil on linen, 21" x 24"

photograph courtesy of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery

SR: I read an essay about Milton Avery where the author repeatedly referred to his mark making as childlike. Roberta Smith used the term in reference to your work in her review of your solo show last April. So I was wondering if that kind of mark making is something you think about.

RK: I think it’s important to see a distinction between childlike and childish. I think “childlike” allows it to be more about the way children view the world, with less prejudice. Things are more open. We haven’t started to lock down our own conceptions of what we expect from reality. So I think the childlike markings… Well, I hope that they encourage a slower engagement–that even if just for a few minutes, it allows the viewer to sit back and contemplate their own realities and how it relates to other people’s realities. I don’t like to be too didactic, but I hope there is still some level of social commentary that I can engage with by not just photo-realistically delivering the subject.

SR: So you want to influence how people abstractly interpret the world.

RK: I want the work to encourage empathy. The experience that painting can engender… I think painting is good at doing that sort of thing.

SR: Can you talk a little bit about how you see paintings encouraging empathy?

RK: Paintings are these things that are consciously presented to a viewer. When you stand in front of a show, I think an indicator of its success is a compelling desire to contemplate why the artist decided to show you this particular group of objects. Painting has this great quiet way of sharing ideas. Looking at an interesting painting is an opportunity to recognize one’s reality in contrast with another’s.

SR: Something your drawings remind me of is an episode of Hidden Brain (an NPR podcast) that included art forgery. They talk about one of the best art forgers in the world. He would get drunk to mimic old master drawings so his marks would remain fluid. That’s because he wasn’t able to be too tight if he was drunk. Your marks are extremely

Garden Pond, 2016

oil on linen, 21" x 24"

photograph courtesy of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery

fluid, even though the drawings you make beforehand tell me that they’re planned out first.

RK: I try to do most of the editing on the drawings. It rarely takes a single preparatory sketch; it usually takes maybe two or three. Once I’ve landed on a drawing that works, the painting seems to almost make itself in a way.

SR: Do you throw a lot of drawings away?

RK: Yeah, I throw away a lot. One in five might turn into a painting. I haven’t been working on site, plein air. I try to experience the locations and then come back to the studio to work through it–what parts of the landscape resonated with me, which things felt compelling. I like sorting through it afterwards. If I’m too worried about making each drawing successful, the resulting paintings turn out stiff.

SR: They’re all pretty thin. What does an editing job look like for you?

RK: Yeah, I do like to let every form contact the linen. I’m interested in that texture.

SR: Is the color of the linen very important?

RK: Its color isn’t necessarily as important as the acknowledgment of the object’s surface. The linen has a different emotional weight to it than the white of the cotton duck. You can just kind of feel it. The cotton duck is a lot more immediately satisfying to work on though. If you mix in just a little extra linseed, you barely have to reload the brush. You can just go forever. I get distracted by the sensuousness of it. The linen requires a bit more paint, and stopping more often to reload the brush has been working for me lately.

Ryan Nord Kitchen in his temporary studio holding a preparatory sketch beside the corresponding finished painting titled Double View

photograph Scott Robinson

SR: And once the shapes are established, you stick with them.

RK: Yes, for the most part. I do the line work first, and then paint in around it. Editing then is limited to covering up or slightly modifying the lines. Adding any new line work is tricky because you can see that it’s picking up the texture of the paint beneath instead of the linen. Edits are usually removing things that feel too literal, anything that is too immediately readable. If something starts looking too legible, that’s got to go–anything that’s too heavy-handed. I want them to remain open to interpretation.

SR: But you do keep landscape references sometimes.

RK: Yeah, even just last year I was using shapes that were easier to read as clouds, some more recognizable horizon lines. I’ll go back and forth, even in the same week. I’ll do one with very clear perspective, and then react with one where it’s buried much deeper. What it really comes down to is if it’s feeling too tight, I can’t really engage with it.

SR: There are lots of historical references I’m picking up. It looks to me like there’s a lot of Bonnard and Vuillard in these.

RK: Oh yeah for sure. Bonnard especially. His textures are just fantastic, and the intimacy.

SR: And there really seems to be a resonance–I’m thinking about the rhythmic quality and the broken lines–between you and Vuilllard. There’s lot of implied line in his work, lots of disconnect.

RK: Yeah, I love those.

Double View, 2016

oil on linen, 15 3/4" x 20"

photograph Scott Robinson

SR: It’s interesting that both you and Paul Klee started out as musicians.

RK: I really have a lot of love for him and how he constructed his compositions, his humor, and the way he handled the surfaces of his work.

SR: Do you feel like you approach color in a similar way? Or how do you use color?

RK: I think there is an emotional register to it, but at the same time, just using it to define disparate elements that compose a picture. Usually, I don’t need more than a few colors. It’s usually straight out of the tube, maybe two or three colors mixed at most. I like the colors to be distinct enough that you can read the individual forms as they work together to bring about this image. So the color is often just a contrast to what’s around it or just evoking harmonies or dissonances depending on what I’m going for on a given day.

As much as I find Gaugin problematic, I do agree with him on how color should never be tied down to representation. I think about the post-impressionist approach, just paint the color that feels right. Use it compositionally, formally. Don’t worry about imitating photo-realistically. For me it’s more a formal issue.

SR: I think about Fragonard’s drawings too. I notice a lot of similarities between your marks and his–but at a different scale. Yours are zoomed in.

RK: I was actually just talking about him the other day with somebody else. He’s got a show coming up at the Met that I’m really looking forward to. But I never would have guessed five years ago that I’d be looking at Rococo. Things have a way of coming up in the studio.

SR: Right. It’s not a movement that feels like it should have much traction, but it can creep in unexpectedly. I remember when Kerry James Marshall came to visit my grad school class at UF, he talked about Rococo’s influence on some of his work.

RK: His use of the history of painting has heavy social implications. The power of his work resides in what some histories so regrettably push under the carpet. He is a great example of someone who is able to work with the expectations we have of painting while injecting a new, engaging layer of commentary. I thought the portion of his show at the Met that he curated from the permanent collection was a great inclusion. I’d love to have an opportunity to do something similar.

Field View 2, 2016

oil on linen, 12" x 15"

photograph courtesy of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery

SR: I see a lot of painting being done now that very clearly points to the past. For example, artists like Matt Kleberg, Loie Hollowel–who recently had a great show up at Feuer Mesler– Sharah Hughes, and Yevgenia Baras–who just had a great show at Nicelle Beauchene. Are there any artists that you feel a particular affinity with?

RK: Yeah, they’re all great painters. There are so many people painting today that are making interesting work. I just saw the Merlin James show at Sikkema Jenkins. I’m a huge fan of his. They’re just fantastic, magical paintings. Patricia Trieb, I love how she uses her references, her compositions, and brushwork. People who can make a lot out of seemingly little.

SR: I’m thinking of a painting of yours I saw at Trestle Projects. It was in a show Will Hutnick and Polly Shindler curated. It felt meta; it was a painting of a drawing of abstract marks. Could you talk about that?

RK: That one was a lot different. Something I had worked on while bridging my earlier pattern-based work and where I am now. I had two paintings in that show from a series of only four or five pieces. I was thinking about handwriting and style guides. Thinking about it now, it seems heavy-handed in evoking the construction of language schemata–how things are what they are. When does this line become a tree for example? When is this line a piece of grass? It’s the ambiguities that I’m interested in. Those paintings were more literally trying to evoke that reading whereas now I’m more comfortable pushing it with maybe even as little as a title. Letting it be fairly abstract but calling it “early morning” or “pond” pushes the reading a certain way. Sometimes a painting can be more effective when it’s subtle.

SR: What’s your favorite kind of weather?

RK: I like rain.

SR: I see you’ve got clouds and rain tattooed on one of your arms. Where’s that from?

RK: Just from a painting. I like how rain sort of levels everything out.

Orchard 1, 2015

oil on linen, 12" x 15"

photograph courtesy of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery

Ryan Nord Kitchen is an artist in Brooklyn, NY. He is represented by Nicelle Beauchene Gallery and has recently been reviewed in the New York Times. He has shown extensively, having his work in exhibitions at Galleri Jacob Bjorn in Denmark, NAM Project Milano, Terrault in Baltimore Contemporary, Rod Barton in London, and Trestle Projects in Brooklyn.

Scott Robinson is an artist in Brooklyn, NY and the founder of Painting Is Dead.

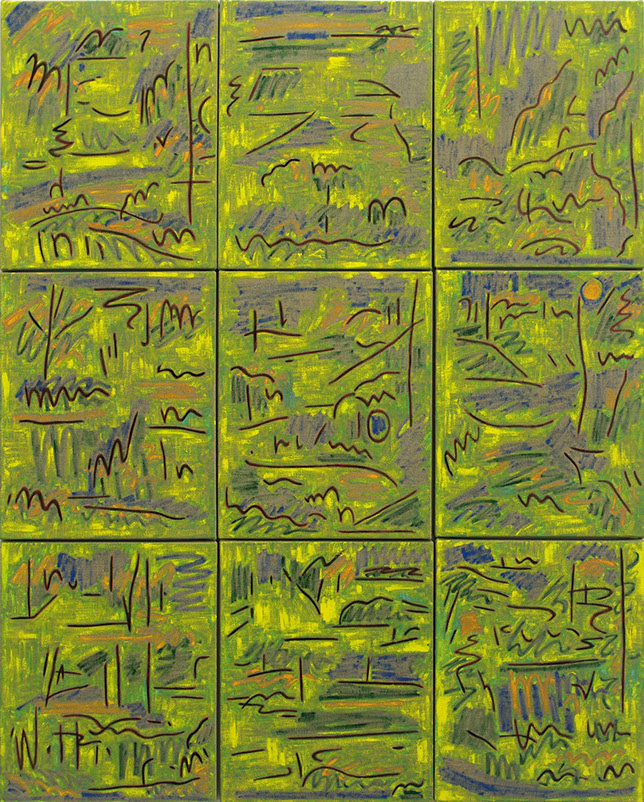

South Slope 3, 2016

oil on linen, 9 panels, 36" x 45"

photograph Scott Robinson

Disclaimer: All views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors, owner, advertisers, other writers or anyone else associated with PAINTING IS DEAD.