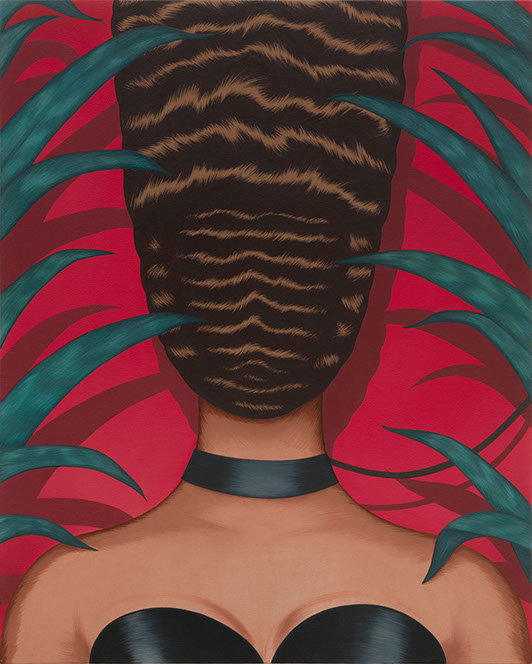

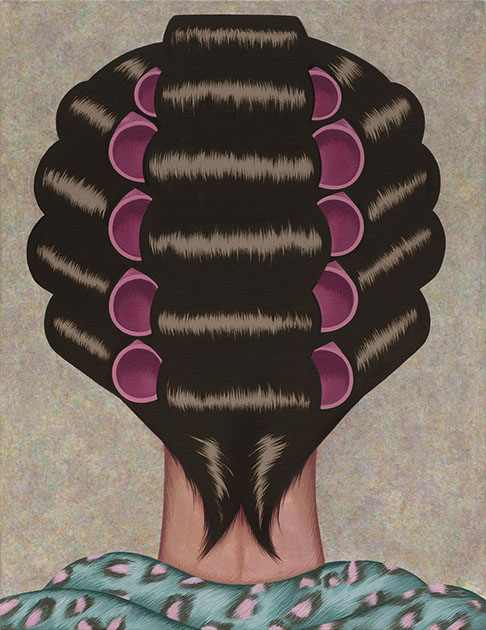

Here Master's Voice, 2016

acrylic and oil on canvas, 40" x 32"

photograph courtesy of Julie Curtiss

Brigitte Mulholland with Julie Curtiss

BM: You’ve had some exciting shows recently!

JC: Yes, there was a big group show about female surrealism. The older generation—Louise Bourgeois to Dorothea Tanning. The newest generation of surrealist painters was in it too—a little bit of me, Loie Hollowell, and Sascha Braunning. Thirty to Forty artists were in it, so it was a big show. I was so excited when I heard about it: “White Cube?! Am I reading this correctly?!” I couldn’t believe it. It was really exciting. I’m really excited. I’m also excited about my show at 106 Greene that ends November 5th.

BM: Amazing! I really like the food paintings that you’ve been doing. They’re really interesting. I love this tart.

Another Piece of Pie, 2017

Acrylic and oil on panel, 24" x 36"

photograph courtesy of Julie Curtiss

JC: Yeah, I tend to do more anthropomorphized things. I objectify women and anthropomorphize objects—like the fish or the tart. I think it relates to what I’ve been working on, which is the body. I used to paint more internal landscapes. The paintings were imaginary worlds and included lots of guts. I really love them. I don’t know if you know my older work? But I felt like I had to transition and start to paint the outside world. I choose objects that give you a door to enter the inside world of the body. The paintings are still very stylized and imaginary, but more about the body now—inside and outside. Food for example, is what you put inside your body to process nourishments. The tart also sort of looks like a slice of vagina.

BM: Yes! That is totally where it went with the tart. The hair is very present in it too.

JC: Exactly. I’m trying to make it look strange. So shape-wise, I think I’m going to actually do a few paintings like the one of the tart. There are a few things I’m not happy about with this one. But that’s ok. From one painting to another, it will evolve. I'll try to improve on the concept in the next one.

BM: Yeah, perfect starts don’t usually happen.

JC: I have stopped wanting to make a piece that says it all. You know? Sometimes making mistakes is important. If you try to put everything into one painting, that’s when you get stuck. You can never remain at the same level. You have to evolve. The stakes are too high, so you can never achieve your ambitions otherwise. This painting is imperfect in its own way, but I’m going to try to say something new in the next one that I couldn’t with the first one.

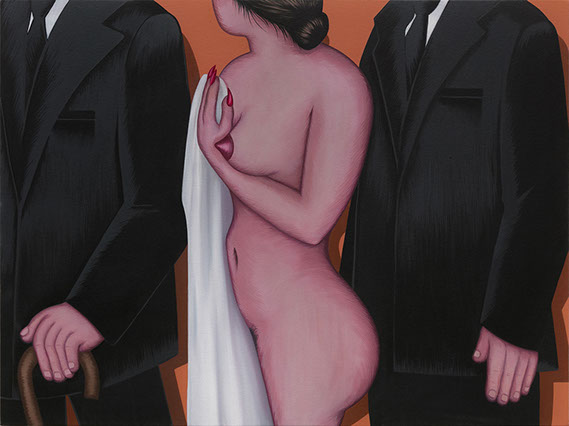

Funeral, 2017

acrylic and oil on canvas, 30" x 40"

photograph courtesy of Julie Curtiss

BM: Your work is so precise. I love it because they’re so feminine, but also a little bit sinister. Like that slice with the sharp edge of the spatula; it’s so sexual. And even the tart itself, like we mentioned earlier.

JC: Would you say aggressive?

BM: No I wouldn’t say aggressive. Sinister I think is the right word. But not in a bad way.

JC: People often say that the hands I make aren’t feminine hands. There’s something masculine about them—kind of fleshy or claw-like. I represent women, but there are always masculine elements in the women. So there is masculinity in my work.

BM: My personal reaction to your work is always that you present a kind of femininity that allows women to be masculine. They’re beautiful paintings, but the women have an edge. I think that’s sort of rare in paintings by women to be honest.

JC: It’s funny because Clint [my husband] came into the studio once, and saw the beginning of Funeral. And he said, “Is it going to be a feminist painting?” There’s a naked woman and she’s sandwiched between two dressed men; and he felt like she was showing something wrong or vulnerable by trying to hide her body.

BM: Well sure, but that is a classic Venus—hiding but still showing.

JC: Yes, and it’s actually after a Courbet painting. It’s a mix of two paintings. The Painters’ Studio—with the woman naked like this and all the dressed men nearby because she’s a model. But I mixed it with another painting from Courbet, A Burial at Ormans. I don’t know, she’s like some kind of… I think it’s kind of psychological. Vulnerable women are not weak women, you know? I’m just showing different sides. That side exists in me, you know? Whether we like it or not, that side exists in me.

BM: Yeah you make it complicated and nuanced because women are complicated; being a woman is complicated. Do you look at Courbet a lot? My favorite painting of yours is the one my friend Ed bought, and that’s after Origine du monde.

JC: For some reason Courbet has never been a huge favorite of mine. But as an inspiration, there’s something about his paintings I can take from. They have something kind of raw and austere, but political at the same time. They have something that’s different. I like Manet as well. Courbet and Manet, I think, are my two big inspirations. It’s funny because I’ve always been a lot more interested in French Impressionists or French 19th and 20th century painting. But I’m also really into painting history in general.

D’apres l’origine du monde, 2016

Acrylic and oil on canvas, 23” x 28”

photograph courtesy of Julie Curtiss

BM: Do you think you’re doing it because the women that they paint are so different?

JC: Yeah! Because Degas for instance, there’s something pretty cat-like in his women. Or Renoir’s figures…

[both laugh]

BM: We don’t need to talk about Renoir!

JC: Ha, yeah… And Monet doesn’t really care about women. I think he’s more into landscapes and haystacks. But Courbet and Manet, there’s something about the women that’s really real.

BM: Really real in a way that I think shocked people, which is why they were so controversial—and awesome.

JC: I like how they seem to smell. The women in the painting have a sour flavor.

BM: Yeah I know what you mean!

JC: They’re very real and that’s exciting. Yeah I think that’s one of the reasons, I never thought about that. I like re-contextualizing these women in the present—re-interpreting Courbet’s women and shifting their meaning. I’m re-painting my own version of these artists’ work and not taking any of their work in their historical context.

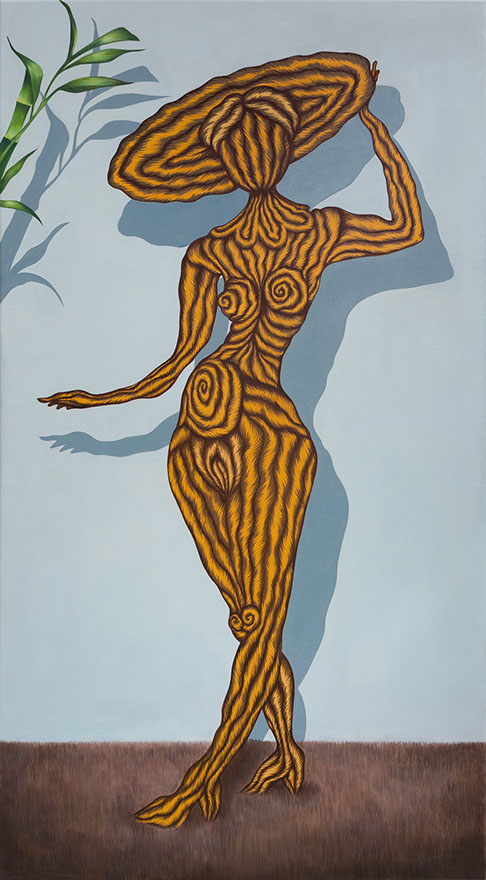

Venus, 2016

acrylic and oil on canvas, 58" x 32"

photograph courtesy of Julie Curtiss

BM: I think a lot of people, well, they look at the masters and they sort of just…

JC: Emulate?

BM: Emulate it yeah, but also it’s still continuing in a certain painting narrative. But yours I think is decidedly trying to avoid those narratives. And for instance, a lot of your marks reference hair, but it’s more than that. Hair is just one word we could use to describe or reference it, but there’s more in it. It feels kind of alive too.

JC: Yeah in the painting I did, Origine du monde, after Courbet, people don’t really call that hair. It looks like something else—some weird raw material. I love hair because I love the substance. Hair doesn’t have a form. It could be shaped. A shape that you can sculpt with, that’s what I like about it. And I like smoke because it’s like hair. It’s very fluid and malleable so you can use it like clay. They don’t have just one form.

BM: Do you think about these paintings sculpturally?

JC: Yeah, and I’ve always done sculpture. When I have more time I want to do a lot more. That’s why I’m excited about the upcoming show in LA. They told me they’re open to including sculptures and the hats. But the works are small so how do I fill a huge gallery? I think I might do a series of braided hats.

But I also feel like all of these are objects—I’m painting objects. There’s no environment in my work. It’s centralized around subject and object. So they all feel like objects that exist in a parallel world. I’m excited to actually make them because I’ll be making these impossible objects tangible. I think it’s interesting and exciting. And it’s funny because I see a Carl D’Alvia and I think that he’s almost doing a 3D version of what I’d like to do in my paintings.

Party Down, 2016

Acrylic and oil on canvas, 40” x 30”

photograph courtesy of Julie Curtiss

BM: The texture, yes—similar approach in style for sure. When you hit a wall, do you look at other work? What do you do when things aren’t working?

JC: I just put it aside. That’s why I want to get started early on upcoming shows, because I know sometimes it’s just immediate—I’m excited about it, I’m doing it like one step two step three step. There’s still some discovery on the way but it’s a pretty simple process. But sometimes I think it will be easy and it just turns out to be really hard, and it takes more time. I need to put it aside and not think about it, and then when I’m really pressed I have to do it. Usually I work to almost 85% and then the last ten, fifteen percent it’s “arrrgghhhh.” You know?

One that was hard to do was Party Down. The problem was starting to work with oil and me not knowing how to work with oil—not being used to have to wait, and then the oils dries so much darker. All that stuff to figure out.

BM: Why did you make the change?

JC: It’s much more vivid. Its less plastic-y. It’s also the blending, you can’t do it well with acrylic. So when I have to make flat surfaces, like here. I should really use acrylic when I draw like this, all the parts that are hair, that definitely needs to be acrylic. But when I do the slight texture here, that’s transparent, I need to use oil. I found that trick. To make the skin more transparent, or something about it is different—the contrast. So not everything is so solid or the same thickness. I need to do these kinds of transitions.

BM: So do you consider yourself a feminist? Do you feel like it’s feminist work or is it something you’re trying to say?

JC: Ugh, my God, that’s a really hard question. On the one hand it’s like yeah, sure I’m a feminist. A lot of people tell me I have to be a feminist painter, but I feel like I’m working on a topic that’s close to me because I’m a woman and I’m interested in women’s psyches and women’s issues, their body, culturally the image of women. But I think there’s so much to tap into there, there’s so much to say. I don’t even know what that means, to be a feminist anymore. There’s now not a single idea of what feminism is.

BM: Yeah there are so many different groups of people, viewpoints, and opinions, sometimes they’re even contradictory. But I see this approach to the complicated in your paintings, and it’s very positive. We as women can be a lot of different things—complex things. And, that’s what it is to just be a woman. That’s that.

JC: And it’s not a political statement that I don’t paint men. It’s an artistic approach. And I mean, there are men in one of the newer paintings, but men are not going to be very present in my work in general. Or who knows? Maybe my work will evolve to only be painted men. Who knows? I was painting bodybuilding women a lot and there’s always an element of masculinity in my women. The animus is in the women and there’s this ambiguous being, or thing to look at. I think there is some content that can be interpreted as political in my work. It’s political in a way that’s very subtle. But I like to keep it open. I think that as soon as you put a strong statement behind something, it becomes trite. As artists, we should keep it open to interpretation rather than make closed statements.

BM: I agree with you.

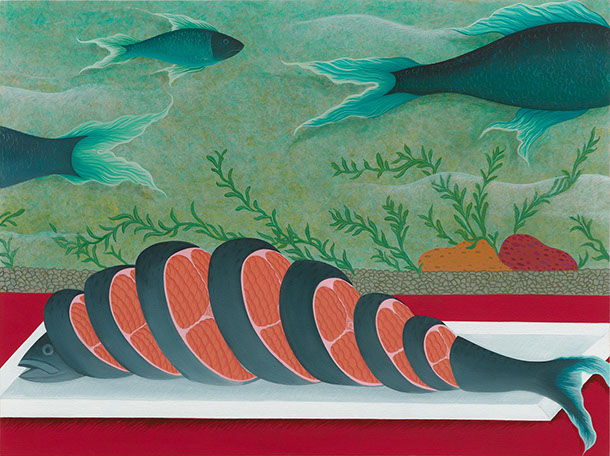

Entrée, 2017

Acrylagouache and oil on panel, 18" x 24"

photograph courtesy of Julie Curtiss

JM: Also, I’m making fun of a lot of female attributes: the long fingernails, the heels, the hair. I’m interested in the complicit part of women. I’m interested in the domesticated woman. In my work, the braided bodies are like the contrasts between the domesticated woman and the “wild” woman, with her claws and her cigarettes. There’s always a tension between the two. The domesticated woman has food, turkey, big breasts. All of that is sort of a joke. But I also understand why they are social norms and why they are social roles. They have a history, you know? We have a history. I like when it’s funny but also beautiful. It appropriates a lot of cultural things—judges but also participates in it.

BM: And kind of subverts it.

JC: Yeah, I am interested in our inner contradictions—how as a woman, I want to be independent and active, but I also want to be protected and worshipped. Now modern women are taking on even more hats, besides being mothers, like professional careers and so on. What is a social construct? What’s biological? Can we override our bodies? It’s complicated.

BM: Do you want to tell me about this fish painting? Because I adore it.

JC: I think it’s dark humor. You know when you go to the Chinese restaurant and you see all the live animals? And then they bring one out on your plate—how that makes you feel? It’s the feeling or idea of sacrifice in this painting. It’s a painting of life and death. You have the illusion of freedom and then, you know, we’re all fishes in a tank, basically. It’s totally me projecting onto the animal. I project onto and anthropomorphize everything, inanimate objects too, but then the fish is not an object, it’s an animal.

Also the slicing… It’s very sculptural, and the flesh is so unrealistic. I started by trying to paint it the way real salmon flesh looks because I like the pattern of it. But I didn’t find the right way to do it, so I decided I was just going to do the same pattern I’ve been doing for so long. I don’t even know what it is. It looks synthetic.

BM: I think I have a really dark sense of humor so that’s why I like it so much.

JC: Yeah it’s totally dark, ironic and sardonic. It’s a bit different, maybe, from the other paintings.

BM: Maybe it’s your technique, but it seems logical to me. It’s different but it’s definitely one of your paintings.

JC: Thanks, that’s what I think too, but people have said, “this is a departure, this is different”. But I see a continuation. Maybe it’s because there’s a background or environment around the subject? Of course there are art dealers who only want me to make hair paintings.

BM: Oh yeah, “Can you make it with a red background in a size that fits perfectly over a couch?”

JC: Yeah.

BM: What do you say to that?

Carapace, 2017

Acrylic on canvas, 26"X20"

photograph courtesy of Julie Curtiss

JC: I say sure, but I’m not going to do it. I want to work with people who really trust the artist: “You know what, you can do what you want.” That’s a vote of confidence and I think it is safer to work with those people. You can trust those people.

BM: There’s a balance between just wanting you to be a factory and actually nourishing your growth.

JC: And I’m learning. Until recently I was just painting in my little studio and it was great— pressure-free. And maybe “Oh cool, I’m showing sometimes, cool”. Now it’s different. Not too different, but I’m definitely learning how to deal with the different ways of being pressured to do something.

BM: New elements are in the studio now.

JC: Yeah it’s changing the whole context of the practice

BM: What are some things in your work you’re thinking about right now?

JC: I feel like I’m pushing my work to the edge of illustration. I’m doing it because I want people to be able to read something—like a narrative. I want them to read something, but make it their own and draw their own conclusions. I want to keep that vague element.

BM: Ambiguity.

JC: Yes, I love ambiguity. It’s my favorite trait. I try to make use of double meanings. For example, when something reads as a body but also tresses of hair or a tart that also looks like a vagina. Have you seen the evolution of my work?

BM: Yeah I’ve been looking at it for a while.

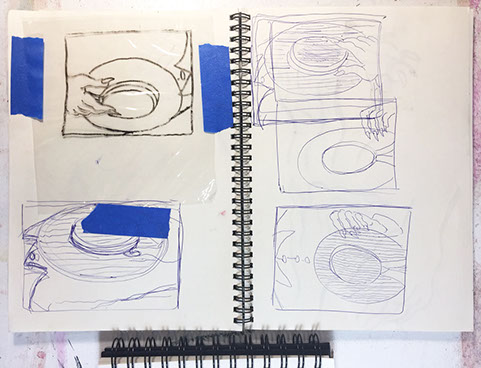

JC: Do you know my small works on paper? That’s where the whole series started. I can’t wait to do more works on paper because it’s a way I can make small ideas quickly, with a lot of energy. People want to buy canvases but it’s really fun for me to make the works on paper.

BM: Do you think of them as studies?

JC: I thought they would be studies at first, but sometimes I just save them when they’re new concepts that I want to use later. And sometimes I feel like I want to just do something different.

Julie Curtiss' prepatory sketches

photograph courtesy of Brigitte Mulholland

BM: And sometimes something works on paper but it doesn’t translate or scale up.

JC: Yeah exactly. And that’s why it took me a while to make the bigger works on canvas, because you can’t translate everything bigger on the larger scale. I don’t always know how big I’m going to go because I feel my work is intimate and I want to keep the intimacy. I don’t know. I think there will be recurring elements I won’t tire of: the hat, and different iterations of the hat could be cool too.

BM: You know, in your fish painting, the end of the tail looks just, subtly, like a little boot. Is that me reading into it?

JC: Oh my god you just gave me an idea for a painting. I like when people tell me what they see. I’m writing the note now, “Brigitte fish tail.” What you saw is so funny. Definitely something is going to happen!

BM: I can’t wait to see it! Thank you so much for the visit, Julie!

Honey moon, 2017

Oil on canvas, 20" x 24"

photograph courtesy of Julie Curtiss

Julie Curtiss earned an MFA from Ecole Nationale Superieur des Beaux-Arts, Paris in 2006 and has been included in group exhibitions at Regina Rex in NY, The White Cube in London, Monya Rowe in FL, The Hole in NY, Spring Break Art Show, and Espace Le Coeur in Paris. Her solo show Soft Shells is at 106 Green Gallery in Brooklyn and closes on November 5th.

Brigitte Mulholland is Associate Director at Anton Kern Gallery, New York, NY

Disclaimer: All views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors, owner, advertisers, other writers or anyone else associated with PAINTING IS DEAD.