Stuart Lorimer in studio

Photo: Scott Robinson 2014

Scott Robinson: The first thing I notice in your studio is that drawings are prolific. They're in stacks on the table. Many are pinned up on the wall. They look like finished pieces rather than studies. Is there a difference between the way you approach your drawings vs. your paintings?

Stuart Lorimer: I don't approach drawing much differently than painting, especially since I’ve been working on canvas that’s tacked straight to the wall. I feel like the movement between my drawing and my painting is now more fluid than it has been.

SR: Where does it start? Is there a typical impetus?

SL: Usually it’s to make a big mess. You have that initial fear of a blank canvas or sheet of paper and I guess I just want to punch my way through it. So I’ll try to pour some paint down so it’s not white. In those early stages I feel quite free to experiment and make more direct genre paintings. The first few coats of paint might look like a shameless ripoff of a Rothko or Newman, then I might put some Guston-like shapes in there before I become self-aware and scrub it back. In this regard, I like to work through my influences in the initial stages of a painting.

SR: Do you change the approach to setting up those problems every time you start a new series?

SL: The biggest problem for me is always that white surface. But yes, the approach does change. Sometimes it is quite a clear decision to start a drawing or a painting with an action or an image. It can be very haphazard and erratic. The drawings lean into figuration, but ultimately relate more to abstraction –though I don’t like to think of painting in those terms.

SR: There was another term you used as we were preparing for the interview.

SL: Yes, I’m looking for a non-linear, more elusive image.

Bright Band, 2014

oil on canvas

62.5" x 63.5"

Photo courtesy of Stuart Lorimer

SR: You seem to flow freely from the impulse to use things that are random –like automatic writing and impulsive marks –and then go back into imagery before returning to subconscious impulse again. Is the tension between abstraction and representation what feels important to you?

SL: I guess so. I get nervous when I use imagery because I can get stuck thinking about what the image is doing –if it distracts from the painting. If I’m working from a photo, how do I manipulate that image to become something that is as unique as a photograph? There is always that contention between the reference image and creating an original picture. These are old painting problems… Perhaps it’s best not to over-think, and make the painting.

SR: I remember at Vermont Studio Center this past February, you used a floor logo –a bee. Another painting looked like you used the markings from a sweater, and you also had a geometric thing. Will you use any type of imagery?

SL: It’s all up for grabs. I do feel tethered –to a degree– to figuration. It feels like it informs the way I work. In terms of the humor behind the work, that’s often derived from figuration. Even in clumsy drawings, they have character.

SR: And you often repeat imagery.

SL: Definitely. That goes back to a professor I had at Tyler [Tyler School of Art, Philadelphia]. I remember a class when he played a CD with ten different versions of Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah. He would encourage us to make ten different versions of a painting. I’ve been doing that with drawings and it has been happening with more frequency in the paintings too. There have been certain motifs that have reoccurred –for instance the little bee figure from Vermont. I’ve carried him around like a talisman or a charm.

SR: There are also some zeros with drips.

SL: Exactly, yeah. I liked those because it’s a continuous shape and your eye can run around it. You can count up from zero or down to zero and I like that flow.

SR: Or it can be a middle point.

SL: And it can too, exactly. It became a thing that I used for a little while. I made maybe three or four decent versions of those paintings. The first one was the best.

SR: Is that rare, that the first is the best?

SL: Actually, it’s usually the case.

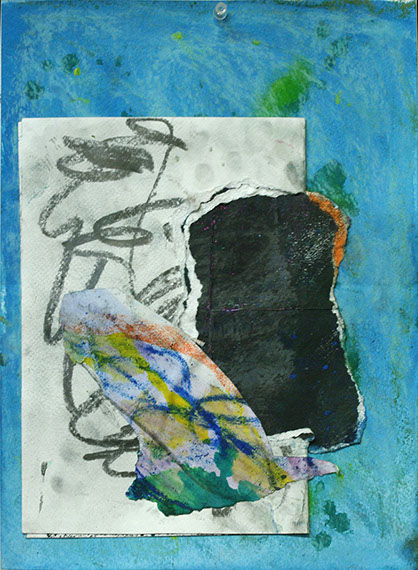

SR: There’s a drawing on the wall that I’m curious about. It looks like a projectile of some sort. Can you tell me about that?

SL: It does and it even looks like it could be a landscape. It’s tough with this type of drawing. It’s so easy to free associate.

Untitled, 2014

acrylic, ink, pastel and graphite on paper

10" x 13"

SR: Is that something you want to discourage?

SL: No, no. In a lot of the work, there are points of reference. It’s sort of the contrail of whatever move I’ve made atan earlier point in the painting. If we’re talking about this painting [in progress on the wall of a man with no arms and a stick between his toes and his mouth], I wouldn’t be at all surprised if it became a dirty, dribbly abstract painting. At one point, this other more abstract painting, [Mackarel Sky, 2014] was very figurative. You can see it here and there. I took the original image from a book I had on my shelf. There was this picture on the sleeve of the book. The book was about the history of film and they made this odd photomontage of [Robert] De Niro’s face in Taxi Driver with Judy Garland. I liked the contrast in the image. It made me think about the way I paint. It seemed natural for me to use that image. Then I had to wrestle with it and see if it could work as a painting. It’s not that I wanted to make it difficult to read, but I just wanted to make something I hadn’t seen before. That’s what it’s all about for me. If it’s surprising to me and I feel like there’s been some conviction in the way it was made then I’m sold. That’s what I look for.

SR: Do you see a relationship between the way you approach painting and the way someone like Michael Berryhill approaches painting –in the sense of searching for mystery or the unknown?

Untiled, 2014

acrylic, ink, pastel and graphite on paper

14" x 15"

SL: Because his work is more representational than mine, I think he’s creating more of a world than I am. You know what I’ve been thinking about –and this is just recently so I don’t really know how I can relate this to the way I paint. It’s just something that’s been nagging me as I’ve been painting and drawing the last couple of months, but I went to see this film The Devils which was playing at BAM. It’s a film by Ken Russell. The art direction is by Derek Jarman. It’s beautifully made. It was made in 1971 and it’s super hammy and a little camp. It was banned in America for a long time. It’s only recently come out on DVD. I’d seen it before, but I watched it alone in my house. I was pretty scared by it though it’s not really a horror but it is challenging and a bit disturbing. When I saw it again in the cinema, the audience was laughing throughout. There was something about the experience of watching that film alone as an individual that was quite unnerving. And then experiencing it as a group –became ridiculous and funny. I love that difference between

a group experience of an artwork and an individual’s relationship with an art piece. You can have a very poignant experience with something and it can also be funny when you’re looking at it with other people. And I think that actually goes for a lot of painting. When you see it with someone else, you can step outside of your personal awareness.

SR: Do you think you get more from film makers than from painters?

SL: No, I think I relate more to painters, but I get a lot from watching films and definitely some of the most vivid art experiences I’ve had are at a picture house.

SR: So if you would, talk some more about your process.

SL: I was speaking about how many times that song Hallelujah has been covered and the value in remaking the same piece many times –looking both forward and backward. So I’ve been going through a lot of old drawings and painting back into them. This artist I work for has a Chris Martin drawing of a cow. It’s a really shitty drawing of a cow. It’s not labored in any way and yet it’s dated in the corner 1978-2008. I thought that was brilliant whether it was true or not. So I’ve been going through all these old drawings and re-working them. For example, this one is probably 2005-2014. I’ve been making these little viewfinders from paper that I paint with acrylic. [The drawings in a large stack on the table] are all made that way. I’ll usually just spend the morning painting sheets of paper. If I have a lot of material –in this process, paper and drawings– then it won’t feel precious to me. And thats liberating in the same way that working un-stretched is very freeing. If it’s not yet an object with weight and depth, then I can do anything to it. And that’s coming off the back of having made a lot of quite precious paintings such as portraits –delicate things on linen. I do really admire craftsmanship in art, but I feel like it’s a hindrance to me because it feels a bit safe. I don’t want to feel safe when I’m making artwork. I actually want to feel like I don’t know really what I’m doing.

SR: I just noticed that these two paintings on your wall are both painted on the same piece of un-stretched canvas.

SL: I’m really into that. I might do more that way. I like comics and I really like graphic novels. I like that there are these cells and the visual progression. I’ve been stretching out large pieces of canvas and making a bunch of paintings on the same length of canvas, one after the other. I’m not thinking of either painting as relating or sharing a narrative or being part of one narrative, but it’s inevitable that they’ll do both, there’ll be slippage between the paintings a bit of back and forth, and I encourage that.

You know, I said that I don’t like to feel safe when I’m making work, but I do feel that it does give me anxiety if I think there isn’t some continuity or consistency. So if the work is pinned up, if I’m working in this mode and there is some back and forth between the paintings, I feel like that gives me at least –even if it’s not true of the finished work– a sense that there’s going to be some continuity between those paintings and that they relate to each other.

It’s good having them flat on the wall because I can really jab away at these things. I can draw on them with hard graphite and there’s no way that I’ll break through.

Untitled, 2014

acrylic, ink, pastel and graphite on paper

11" x 13"

SR: Some of the area in-between these unfinished paintings or cells on your wall is pretty seductive.

SL: Actually, there you go. Maybe that would be a cool painting if I just stretched that. That’s a great idea actually.

SR: So anything that gives you a surprise or creates a struggle is something that you want.

SL: I have this collection of books that I got from this Temple (Neasden Temple) in London. It’s considered a treasure of the city but it’s hard to get to. They have all these school books that haven’t been updated since, you know, forever. The illustrations are kind of crappy for the most part.

SR: And is this written in Hindi?

SL: Yeah. You know, I can’t obviously read the text and the illustrations obviously illustrate

the text, but what I love about it that I can’t figure out what these illustrations are illustrating. I can’t read the text and the culture is alien to me. I love that. I love that they have a very clear purpose because they’re in these children’s educational books. So they’re not supposed to be enigmatic but the pictures still don’t transcend the language. You sort of know what the pictures are getting at but you don’t really. That’s something I like in painting.

Mackerel Sky, 2014

oil, acrylic, spray paint on canvas

49.5" x 65"

Photo courtesy of Stuart Lorimer

SR: It looks like making this work is a lot of fun.

SL: I feel like it’s opened up a lot more for me now than it has in the past. I’m probably more accepting. I’m more open minded. I’m less hung up on working in one particular mode.

SR: Is there anyone who you feel like has been a guide for you or is this totally a personal development?

SL: It feels pretty personal. As far as artists I like, there’s a bunch, but lately Charline Von Heyl, Jason Fox, Nicole Eisenman, Dona Nelson, Michael Williams, Daniel Hesidence and Susan Te Kahurangi King –an outsider from New Zealand. Her show at Andrew Edlin is unbelieveable.

SR: You just started Bannerette. How do you expect running a gallery to effect your practice?

SL: Whenever you go and see work, if it’s something you responded to, then that’s probably going to impact your studio practice. It might give you no formal or conceptual ideas, but if you see an artist you like it certainly gives you energy/motivation.

SR: You’re interested in how that expresses itself subconsciously.

SL: Exactly, and being able to put on shows of artists that you like generates that energy for me and for Emily (Davidson) as well. So that’s exciting. And we both love meeting other artists and working with them. It’s exciting for that reason. It’s exhausting, but it’s something that we’re both passionate about.

The fun thing about painting is that you can do anything. It’s not like I’m building something (I build things for people where I have to apply a strategy). In painting it’s a whole platform where I can work that doesn’t require strategy. I can do one thing and then I can do the exact opposite two minutes later. And that’s exciting. And it very rarely results in a good painting but you know, one out of ten isn’t bad.

Decommissioned Words, 2014

Acrylic and Ink on paper

17.5" x 13.5"

Photo courtesy of Stuart Lorimer

Stuart Lorimer lives and works in Brooklyn, NY

Scott Robinson is an artist living and working in Brooklyn, NY. He is the founder of PAINTING IS DEAD www.scottrobinsonartist.com

Disclaimer: All views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors, owner, advertisers, other writers or anyone else associated with PAINTING IS DEAD.