Rachael Wren in studio

Photo: Scott Robinson 2014

SR: There’s a sense of space in your paintings, but it feels tactile.

RW: I have always liked the idea that in painting you can make space visible. It’s something that you just move through without thinking about in real life, but in painting, it can be an actual thing. It is a color. It is a feeling. I think of the space in my paintings as a tangible presence, as real of a thing as an object. That came out of my experience living in Seattle, where the air often feels dense and palpable.

SR: So it’s directly connected to nature.

RW: Right. The color relationships and sense of atmosphere in the paintings usually begin with something I’ve seen in the natural world. In the studio, those things get put into a geometric structure. For me, the geometry helps to anchor the ephemeral moments I find in nature.

SR: So how did you come to this? How did this work develop?

RW: The paintings that I’m making now follow a thread that began when I was in graduate school at the University of Washington. Then, I was painting trees outside in the landscape. I was using them as vertical markers of space to help me move back into the space of the painting. I was also thinking about weaving together the spaces between the trees with the trees themselves. Over the years, I stopped painting from observation and the trees dissolved and became more geometric forms within a haze of atmosphere and light. But many of the ideas about structure and space that I was concerned with then are still important to me.

When I was making the tree paintings in Seattle, I was standing on a path that went down into a ravine that had huge trees growing out of it. I was in the middle, so I couldn’t see the tops or the bottoms of the trees, just a cross section of trunks and branches. That’s why in those early paintings it’s hard to locate yourself.

SR: I think it’s still hard in your current work.

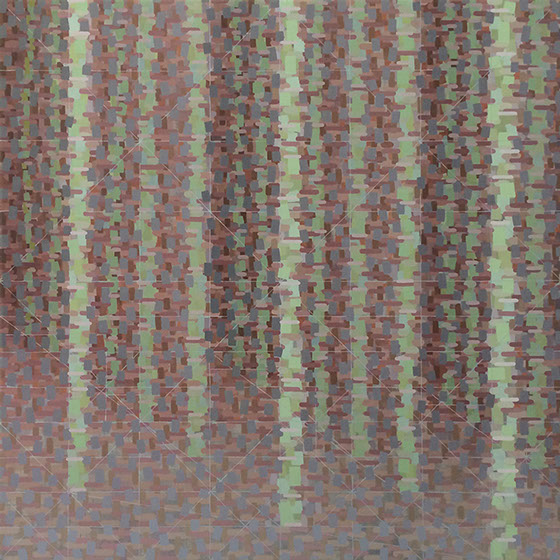

Old Growth, 2014

oil on linen, 48"x48"

Photo: courtesy of Rachael Wren

RW: Yes, that’s true. I’m still interested in that sort of tangle of form and space. You’re not quite sure where to enter the painting. I think the tension between perspectival space and geometric space adds to that as well. The ‘trees’ or rectangular forms in my current work seem to recede as they go back into space –inviting you in– but the grid returns you to the surface of the painting.

SR: Do you know Jake Berthot’s work? Is he an influence?

RW: Yes, he’s been one of my favorite painters for a long time. I was very fortunate to study with him at the International School of Art in Italy the summer after I graduated from college. I had been familiar with his work before that, and it was amazing to have the chance to work with him and hear him talk about painting.

SR: How is your approach to painting different than his?

RW: In a way, we came at things from opposite directions because the work that I was doing at first was more landscape based and over time some geometry came in, and his work started off more purely about the geometry and then the trees came in, but there’s probably some point of overlap in the middle where we both have the same ratio of tree to geometry.

SR: Would you say nature is your biggest influence?

RW: My experience of nature is usually what makes me want to paint. Specific moments outdoors will spark something that I want to explore in paint. Sometimes that initial inspiration carries all the way through and sometimes it’s only a beginning point and the painting takes off in another direction. But it always feels important to have a connection to some sort of lived experience outside of the studio.

There was a period of time a few years ago when my paintings went more towards purely geometric abstraction, without referring to anything outside of themselves. I was excited about that for a while, but ultimately felt like I lost my connection to the thing that I really care about. Bringing back some of my relationship to nature seemed essential. So about a year and a half ago, I went back to looking at trees again, and drawing from them. I had been working with the grid for a while and wanted to introduce something more irregular and organic again.

SR: It’s strange for me to think of these as organic because they look

Studio of Rachael Wren

Photo: Scott Robinson 2014

so technical.

RW: I can definitely see why you say that, and the truth is I’m still figuring out how much I want to break up the geometry and let the paintings feel more natural or ‘landscape-y’. Right now, I’ve done more of that exploration in drawing than in painting. These are some drawings that I did outside, looking at trees. I wanted to see what kind of structure I could find in nature, something to take me away from the grid. But when I brought them back to the studio, I started ‘geometricizing’ what I had found. So I’m definitely still going back and forth between the two approaches.

SR: The drawings that you did on site remind me of cuneiform or music.

RW: Music, yes, other people have said that too. I guess it’s the fact that the spacing is more irregular. And the marks look like a kind of notation.

SR: How important is drawing?

RW: It’s very important for me. It’s often where I come up with new ideas or work through problems that I’m having in a painting. It’s also usually how I figure out the structures that I’m going to work with in my paintings.

SR: Do you find more freedom when you are drawing?

RW: Yes, typically. I often let myself do things in drawings that I’m not yet ready to do in paintings. It usually has to do with paring things down in a way that works for me on paper but I can’t yet believe in for the paintings.

SR: Do you hike?

RW: As much as I can, though it’s not as easy to do or as exciting near New York as it was in Washington.

SR: What was the most interesting hike you ever did?

RW: One that really stands out is an overnight camping and hiking trip I did with some friends in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness in the Cascades. It was the middle of summer, but there was still snow in some places. At one point, we had to cross a snow field that sloped steeply down to an icy lake. I was terrified that I was going to slip and fall and end up in the freezing cold water.

SR: That sense of the ground being totally unreliable is in your paintings. This web of lines is the only structure that makes it solid. The ground is kind of implied by the perspective of these receding trees.

RW: The ground is usually the least interesting part to me and I don’t always know what to do with it, which may be why it feels unstable. I don’t what to paint it as a solid ground plane. Somehow that would seem too obvious.

SR: The support seems to come from the sky rather than the ground. It’s anchored from above. The trees seem to be holding whatever flimsy stuff is beneath.

RW: Hmm, I like the way you put that.

SR: What about digital imagery? Does that have any influence on your work?

RW: It probably does subconsciously but I don’t really think about it when I’m painting. It’s true that my work is made up of small pieces coming together to make a whole image, like pixels, but my intention isn’t to reference digital imagery. Maybe that kind of visual information is such a part of life right now though, that it seeps in.

SR: I hear a lot about how digital images have ubiquitous influence. There’s no eliminating it. Image saturation is part of observational experience.

RW: Right, you just understand the way information is put together. And who knows, maybe I wouldn’t have made paintings like this if I had never seen a computer image.

SR: A lot of artists I talk to feel more free to experiment within a set of restrictions.

Is it important for you to have a very restricted set of rules that govern your process?

RW: Yes, I know that idea, ‘freedom through limitations’. That definitely works for me and I do feel that by limiting the language I use, I can explore more deeply. But I try to question my ‘rules’ because I don’t want to keep making the same thing over and over again either. The changes that I make are usually incremental, but they feel significant to me.

SR: So how do you use the grid? It doesn’t look totally systematic. How do you come up with the lines, they seem to be based on your drawings. Do you intuit these different diagonals? Some split and some don’t…

RW: Well, it is sort of systematic. I guess it’s my own system. I use the grid as a way to place the verticals and also to determine where to shift the color. But the way that the brush marks are put down is random or intuitive. The diagonals are a pretty recent development and I’m using them to find places for the verticals that might not fall exactly on the grid. Also, they make visual connections or paths back into the space.

SR: Have the grids has always been part of your work?

RW: The grid has been there for a long time. When I stopped working from observation, I started using the grid. It seemed like a good way to organize things. When you’re not looking at the world, where do you start? The grid made sense.

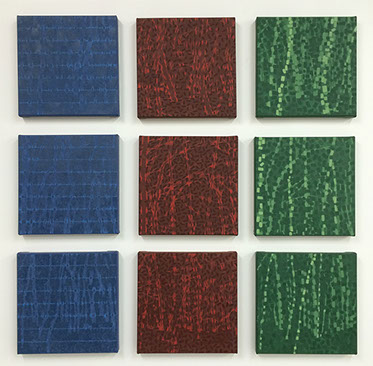

SR: You also have paintings in here that look like were just started.

RW: This is a separate group of paintings and it’s for the Ligo Project, which is a program that pairs artists and scientists together for collaboration. I’ve been working with a scientist who does cancer research at Memorial Sloan Kettering. I visited her lab a couple of times and she came to my studio. Now I’m working on these paintings in response to some things that she showed me in the lab and explained to me about her work. We were looking at cells through the microscope and I saw how they use different color stains and filters to see different aspects of the cells, different proteins. So I started thinking abut the idea that each color or light could reveal something distinct about the structure of an image. I’m working with that concept in these nine paintings – three structures, three different versions of each. We’ll see how it turns out.

SR: How were you chosen for the Ligo project and how long has it been going on for?

RW: I applied for it. I’ve been really interested in the intersection of art and science. We met for the first time in April and there’s going to be an exhibit of the finished work

Paintings in progress for the Ligo Project, 2014

Photo: courtesy of Rachael Wren

in December. There are six artist-scientist pairs in this year’s program. It’s great that we have the time for a lot of interaction with the scientists and that there are no requirements for what we end up creating. It’s very open-ended, we’re just supposed to make something inspired by the science, whatever that happens to be.

SR: So how do you usually start a painting?

RW: I usually start with some kind of drawing about the structure, like where things are going to be placed on the grid. Sometimes those things move around, but structure is usually one of the things I know early on. I also try to begin with a sense of the color-feeling that I’m going for, though the color develops as I’m painting and sometimes it changes a lot from my initial idea. Outlook, for example, has a lot of reds and oranges, but it started out being green and brown. That was a dramatic shift.

SR: There’s something nice about how these paintings start with washes and dry brushed marks. Is that going to disappear as your marks build up?

RW: It might. I do see that there is something nice about them and I’m wondering how to keep some of that looseness for longer. I have been using an accumulation of small, individual, hard-edged marks for a long time. It was interesting for me to try to create a sense of atmosphere with them, rather than with fuzzy marks. But now I’m starting to think that maybe I can let go of some of that idea and have some washy areas in the paintings too.

SR: Does the composition ever start from something that you have observed from a specific color that you want to then transfer into a composition? Or is it usually grid based and then intuitive?

RW: The ideas for color and structure usually start off separately and I bring them together in the painting. The color is the most intuitive part.

SR: Do you think about color theory or are your choices based on experience and memory?

RW: Probably a combination. I’ve taken color theory and I’ve taught it. When I started teaching painting I started understanding color so much better. The way I put colors together now is a lot more complex than it used to be. I’m very interested in optical color mixture, the way small bits of color work next to each other and how those colors start to vibrate.

SR: What I love is when I mix a color and I can put it in three different places on the canvas and have three different colors. It is magical.

RW: Exactly. And that happens all of the time, and I love it. It never gets old.

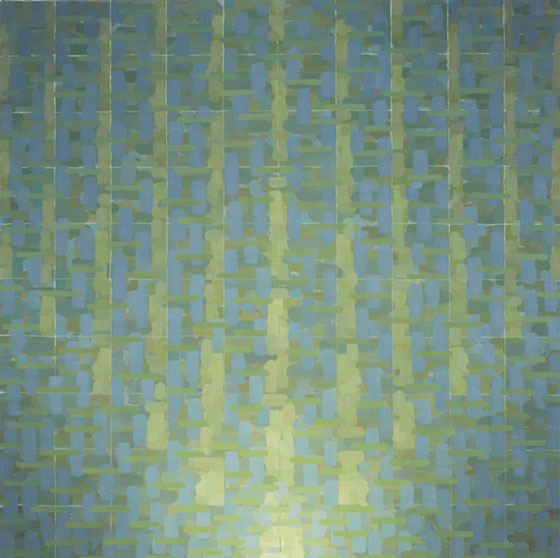

Marsh, 2012

oil on linen, 20"x20"

Photo: courtesy of Rachael Wren

SR: How do you see your work in comparison to Op Art? Is Bridget Riley an influence?

RW: I like her work. In some of my earlier work, I had an optical curving thing going on so there was definitely some relationship to her paintings. I think the difference is that, with Op Art that was the goal, they were starting out trying to achieve an optical effect. For me, it was a bi-product. I was actually surprised when those things started happening. It had to do with the color relationships.

SR: But you were happy about it?

RW: Yeah, it was a nice surprise.

SR: How often do you carry around a sketch pad?

RW: You know, it’s been a really long time since I have just gone out with a sketchbook and drawn from observation. I used to love doing that, but now if I want to remember something, I’ll usually take a picture.

SR: What do you think that effect has on it. Because pictures distort things so much. They don’t record color accurately, etc.

RW: Yeah, you take away something different with a photograph. Usually for me, I just want it to trigger my memory, but it probably distorts it as well.

SR: There is a sense of time or slowness in your paintings that is very different from taking a snapshot.

RW: I’m glad you said that, it’s something I feel is important about my work. That sense of time comes from my process of building up the paintings layer by layer, I think. They are slow paintings – slow to make and hopefully slow to look at, in the sense that the longer you look at them for the more you see. I love the way that time in painting is different from time anywhere else.

Group of unfinished paintings in studio of Rachael Wren

Photo: Scott Robinson 2014

Rachael Wren lives and works in Brooklyn, NY

Scott Robinson is an artist living and working in Brooklyn, NY. He is the founder of PAINTING IS DEAD www.scottrobinsonartist.com

Disclaimer: All views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors, owner, advertisers, other writers or anyone else associated with PAINTING IS DEAD.