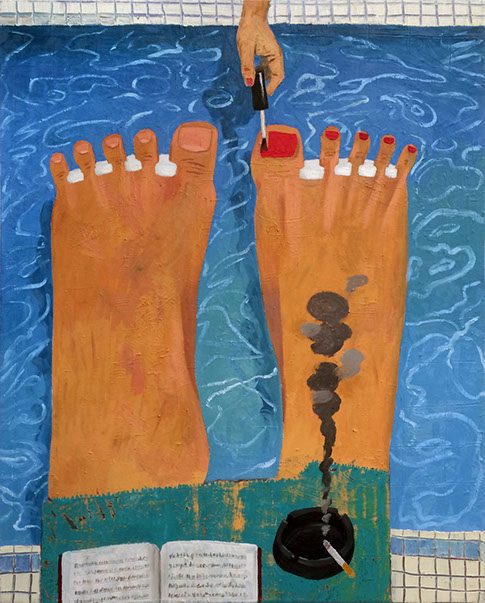

Phil's Pedicure, 2016

oil on canvas, 44" x 48"

photograph courtesy of Paul Gagner

Michael Levin with Paul Gagner

Mike: Let's go back to talking about the Dr. Mosely paintings, where they came from and what motivations you had.

Paul: Sure. Well, the short, maybe slightly uninteresting answer to that question is that they were born from a very literal space limitation. Transmitter—a gallery in Bushwick—asked me to participate in their booth at Select Art Fair. They wanted to pack a bunch of artists in their booth, so they limited the size of each piece of art to something roughly the size of a book, or slightly larger than a book. And that's how it was presented to me. They wanted me, I think every artist, to submit two pieces. So I thought, I'll do a book, because it’s about the size of an actual book. That’s the short answer. The more complicated answer to "why a book painting," is that I was always interested in self-help books. Years ago– eighteen, nineteen, twenty– I was a kind of confused individual, and you know other times, I'm always confused. [laughs] But there's been some times when I've been particularly confused, and self-help books have been there to comfort.

ML: Have you actually read them?

PG: Oh sure, a bunch!

ML: It’s not just a source of inspiration or a curiosity?

PG: Oh definitely, and some of them, there's some really good information in them. Some are just, you know, terrible.

ML: Yeah, I mostly know them as something my mom would give me. And when it’s from someone who has something to tell you, it feels different from saying, "I'm lost, and on my own agenda, I'm going to pick up a self-help book."

PG: Yeah, I've very intentionally gone and sought out self-help books. I haven't read one probably for several years now, but sometimes they are helpful. They're often written from the perspective of a doctor from whatever—teaches at Harvard or something—and it’s research-based; it’s drenched in legit research, you know, some really really good information. Then there's a lot of the cheese—really, really horrible fluff...

Hexes, Curses, and Spells, 2016

oil on canvas, 11" x 14"

photograph courtesy of Paul Gagner

ML: Popularizing stuff?

PG: Yeah. And you can Imagine the author sort of cranking them out, and this is what they do: “I'm a self-help guru.” And a lot of that stuff is just terrible, awful stuff.

ML: I like knowing that you were at least at one point a self-help reader. Are these paintings akin to that act of searching out the self-help book, that you create the book you're looking for?

PG: They're meant to help me.

ML: So the painting is its own self-help book really. It’s not just a cover to a fictional object.

PG: They're meant to be therapeutic, I mean, as much as a painting can be therapeutic. On the one hand, I guess I know that there's a lot of these problems and anxieties that a good deal of other artists have. I'm not unique in having my own little anxieties and fears and whatnot. These are common to being an artist, to the act of creating. It just kind of comes with the territory. I'm not sure that I wouldn't want these things to actually exist, I'm not sure what that would mean for someone to pick up a book hoping that you can hypnotize a curator [laughs].

Mike: I have to say there's something immediately appealing about it, which is what makes me like Hexes Curses and Spells for Your Enemies so much. All of these paintings promise this supernatural advantage in the art world. You're right. You're not unique. There's so many artists, myself included, who are craving that. There's this sort of magical thinking when you have friends who are successful, "what magic are they using?! How do they do it?!" The paintings then become these totemic things.

PG: Yeah, I mean some of it, I imagine it'd be hard to write a whole book about this.

ML: I'm sure it could happen. As the ranks of artists swell, these kinds of books will actually come into existence.

PG: Yeah, God, they might!

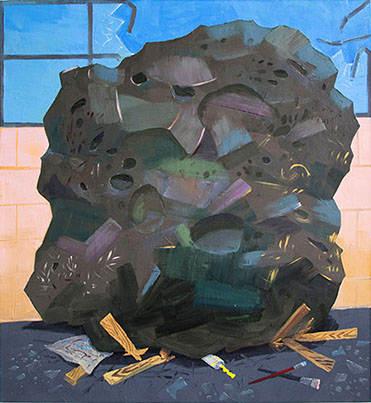

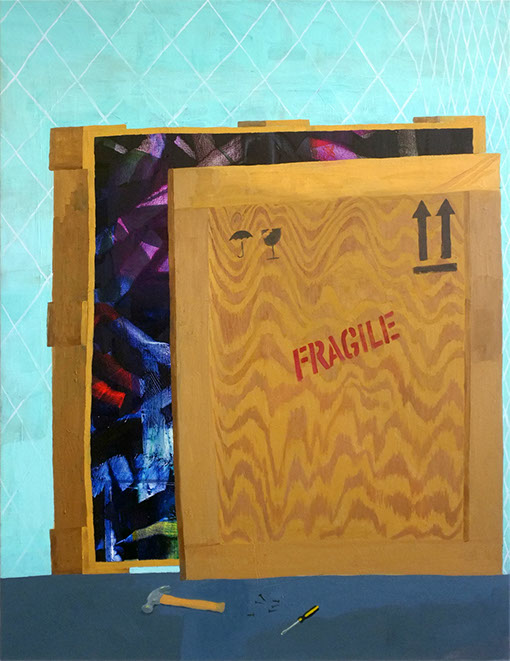

ML: The thing about the Dr. Moseley paintings actually working as therapy for you takes me to another question. It’s about the painting you made of a painting in the garbage, Starry Night, and also Crate—a painting of a painting getting crated. There's the idea of the painting that asserts itself as an object. It’s the idea that a painting should not act like a window into some elsewhere, but be a thing in its own right. What I thought was so funny about Starry Night and Crate is that they are paintings of paintings as objects. They are a window onto a painting that is an object. You're almost double dipping, getting to have your cake and eat it too. You're getting to make an illusionistic painting, while nodding to the idea that a painting has to assert itself as an object. Not really a question, I guess. [laughs]

PG: Yeah, you know those paintings came about really accidentally. I don't do it so much anymore, but for a while I was–well I guess I still do this–whenever I have a white canvas, a blank surface like this, it’s a bit intimidating and scary for this thing to be white and staring back at you.

ML: Do you start white, do you put on a color ground?

Yellow Centers, 1999

Mixed media, 5" x 3"

photograph courtesy of Paul Gagner

PG: No, I just have a blank white gessoed surface and I just start smearing paint on it. I had this professor back in SVA named Joo Chung. I was in the illustration department, and he wasn't really an illustrator, really none of the professors were, but more like straddling fine art and illustration. But he said that he also hated that white surface, so the first thing he would do was fuck up the surface. Throw paint on it, spill it, you know, smear it, whatever, walk on it, anything to fuck it up. He'd make it so ugly, like hideous, at least that's how I imagined it, and then his job from there was to fix the painting. That's how he put it. It wasn't finished until it was fixed. And I thought, God, that’s such a wonderful metaphor, to think about how to approach a painting. Otherwise, you know, we're drawing and we imagine something on it, but it introduces this kind of accident and this disregard to it, and then his perspective is, well he could almost be looked at as a decorator, like he's moving this around, but I like to think about him taking something so ugly and unwanted.

ML: Like it’s some kind of orphan...

PG: Exactly! And like rescuing it.

ML: It reminds me of the socialist realist Jack Levine, who would always say "work fast and make mistakes." But looking at your work, I actually thought that these paintings were planned or premeditated. This sounds like a very different approach.

PG: Well, I should clarify, because your original question was about the object-ness of those paintings.

ML: Yes. [laughs] thank you.

PG: My method used to be more like my professor back then, just smearing and pushing, and at the time I was even just putting a lot of dry paint on just to build up a surface, and for me it was like, I rarely start off with any kind of idea of what I'm gonna do. Sometimes I do, or I change halfway through and abandon whatever it was I had started, but for me it was, well, I'm gonna start painting and just dive in and start pushing paint around. And so it was a way to forget about the starting part–which is another phobia, not that it’s that strong, but another anxiety, but like "oh what do you do with this?" But if it’s already fucked up, you can only make it better. It makes that anxiety a little less oppressive. I mean, it can't get any worse! And so, those paintings, what you see with the smears and that kind of faux-Gerhard Richter abstraction, is that process of just smearing paint, and scraping, doing whatever, just to...

ML: So these bits of abstraction are genuine? You're not sitting there trying to emulate Richter?

PG: No, that's me, if I were an abstract painter that's how I would paint.

ML: And you'd just end it there?

PG: Yeah, but they suck! I don't think that they're that interesting. I don't think anyone would ever talk to me or pay attention to me if that's the only thing I ever showed. I don't think they have enough of that je ne sais quoi that a painting needs to warrant attention. But they're edge-to-edge, that smeary mess is how the whole painting looks at first. Then inevitably I'm staring at this thing, and for me—and this is an interesting problem about narrative—there is no narrative in that, or not a typical narrative at least. There's that narrative of me fretting and working this thing, but, the painting is just a vacuum.

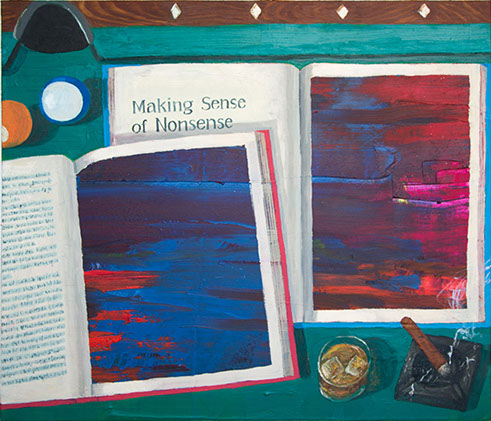

Making Sense of Nonsense, 2015

oil on canvas, 30" x 26"

photograph courtesy of Paul Gagner

ML: Sometimes I look at a painter who does abstract work, that's very free, which I think for anyone that does figuration, the idea of freedom is this kind of remote island that other people live on. And I’m like, "I have to make an arm or a leg or someone doing something" or whatever. But you make that abstract painting and you have that feeling that it’s not enough. Which then strikes me as this kind of self-questioning. So first of all, I want to know how you feel about doubt and anxiety writ large, but more directly I want to know, do you wish you were capable of just stopping the doubt right there, and letting it be an abstract painting, and be living your life?

PG: [laughs] That's really... that's good. I do. The first painters, the ones I have the strongest affinity and love towards, are abstract painters, like Pollock. I adore Pollock and have since I was a teenager, even though I never saw a Pollock until I was in my mid 20s or something. But so much of that love is surrounded in the aura of the abstract painter, which is something I love to fuck with as well, the tortured person. You know, I'm self-deprecating so I love to poke fun at that. It’s so easy to make fun of. I'm losing sight of the question here…

ML: Well, that is the question. Is the abstract painting within your painting this kind of “kill your gods” Oedipal thing, or is it—well, I'm not even sure these are separate things—is it trying to become the thing that you love, but your inevitable impulse is to destroy it?

PG: Yes, I mean, I definitely, even literally, have been attacking heroes. Pablo's Makeover is obviously supposed to be Picasso, and this, Phil’s Pedicure is supposed to be Guston's feet.

ML: Guston has been hanging heavy in the air, ever since I started thinking about this interview, and I also just saw the Guston show at Hauser and Wirth.

PG: So good!

ML: So tell me about Guston.

PG: You know it’s funny, I hated Guston when I first saw him. His paintings are so challenging, they sort of dare you to like them. They're so ugly and awkward and you feel like no one in their right mind would come to them with open arms, they're kind of aggressively ugly paintings—not all of them, but a portion of them. So it took me years to understand that, yes, there's the paint-handling part of it, which is something, a barrier that people can't get past, but then there's everything else. It’s so rich—rich with doubt, rich with anxiety, fear, anger. They're contradictory, they're really weird. It’s not a surprise that people have taken to them, that he's so popular nowadays. I think there is a lot of that same feeling towards the world, towards the art world too.

ML: Do you think that's an honest posture? Do you think that's what makes it compelling?

PG: Well, what I've learned from seeing Guston, and how it’s changed my perspective on painting and art in general, is that I love awkward moments. I love painting that's flawed, art that's flawed. I think it’s the perfection that I feel is very suspect. Like something that's really big and shiny and polished and you don't see the hand of the artist. I mean there's something valid to that too, but I'm not smitten with that kind of work. I want to see flaws. I want to see the artist's hand in it. I think that ugliness is something that we're all capable of, we all have, and so it’s only natural that we would see it. And it’s the artist that's too smart, too controlled that's...

ML: Is it withholding?

PG: That's a good way to put it, withholding, I feel it’s highly suspect. Maybe not so much insincerity, I'm sure that those artists are sincere, and who am I to say that they're not?

ML: There's an unwillingness to be revealed?

PG: Yeah, I want people to expose themselves. I think one thing art has universally in common is exposing oneself, and that kind of honesty, we should see it. It’s the artist that's too calculated, too controlled that feels inauthentic, and it could be anybody. We want to talk about people being individuals, unique. Their particular perspective on art should come through or else it’s a bit pointless, not particularly honest or sincere.

ML: So wanting to be less calculating and less controlled, does that affect the way you handle paint?

PG: Certainly. I fully embrace awkwardness, I really like awkwardness. I mean, I don't really like awkwardness. Social situations can be incredibly painful. You start to sweat, you just want to run away. But in my painting, the awkwardness gets back to the object-ness I like when things get too close to the edge of the painting—where they start to break those codes that you're taught for composition. Or at least that I was taught as an illustrator.

ML: Like John Baldessari's bad photos?

PG: Yeah, right exactly! I love Baldessari and I love those. We have these agreed-upon rules,

Occupational Hazards, 2015

oil on canvas, 44" x 48"

photograph courtesy of Paul Gagner

you just don't go there, and very few people ask "why don't you go there"? He really went there. Those photos are fantastic. I maybe occasionally go there with being a little too close to the edge, or a little too this or a little too that. I especially love the edges, like when things run off the edge in this awkward sort of way, I think it draws attention to its object-ness.

ML: There is a limit to this particular vision, and that limit is the edge of the painting?

PG: Yeah, and I think about photography too. My wife is a photographer. We have conversations when she photographs a person and she thinks the photograph failed because she cut off the hand. But I like that! There's a tension there. I understand what she means. There are calculations and rules that we're taught, and sometimes they’re appropriate and sometimes not. But I think oftentimes—with her photographs or my paintings—if things are cut off it creates tension, a reminder that this is a painting, or a photograph, that these things are illusionistic.

ML: Do you think the self-help paintings are a counterpoint to that kind of awkwardness?

PG: Well, they were painted quite literally to be objects. I never paint the edges, you know, the sides of the painting. With these, the spines are painted, what's supposed to be the pages are also painted.

ML: My interpretation, for what its worth, is that you're transposing the awkwardness onto the artist. Because then the artist, the questioner, is the thwarted individual who needs this kind of magic or self-help or therapy to achieve. But the paintings themselves lack the awkwardness.

PG: Yeah! They do have less of the formal awkwardness the other paintings do. They're a little more polished. They tickle the illustrator in me. You'd probably never get it from looking at these paintings, but I have a formal training as a graphic designer. I went to a two-year school in Madison, WI for graphic design and then transferred to SVA to get my Bachelor's in Illustration. So that’s my day job. I make money as a graphic designer. I have a, well, yeah, a love for typography. I'm not a die-hard graphic designer. But yeah, it tickles, you know. Up until these books I didn't really have an outlet for that in painting. The books came around then I was like "Oh! The graphic design can finally enter the paintings!" And so there's been that kind of dorkiness that's come out.

ML: Do you think the graphic design is antithetical to the painting?

PG: No, I think graphic design was one of the few smart things that I've done in my life. Graphic design—I don't want to keep using the same words, "tickle"—but it’s satisfying, it’s a creative outlet, but it doesn't conflict with painting. So my graphic design utilizes certain creative juices, and so I like it on its own. I wouldn't say I have a great love for it exactly, it’s just another one of my interests.

ML: So to shift gears a little bit: the question of what humor can do in paintings has been asked so many times, so I want to ask instead if there is anything you think humor can't do in a painting.

PG: I like that question. There are some problems with humor, and I'm starting to experience them. One is that it can be read as a one-liner. And sometimes the book paintings are read that way. Many artists that use humor have a similar sort of fear. However, I think of Eric Yahnker, who has really embraced the one-liner. I do like his stuff, but it’s a little catty and snarky. There's some of his stuff that's really great, but I didn't want the humor to be front and center, and support it by pouring a lot of time into it. I feel like that’s what he does. I love humor, but snarkiness is where I draw the line. And mocking, I'm not really interested in mocking people. Some people have asked me with the abstract paintings, why I don’t copy someone else's abstract paintings and I think that would turn into mocking them.

ML: As opposed to this Richter-lite straw-man?

PG: Yeah, and they were always meant to be my abstract paintings. [Laughs] All about me! But my humor can sometimes come dangerously close to being ironic or one-linerish. I am conscious not to be ironic because it feels detached, cool. I want it to be clear how I feel, and what my stance is—which is why the book paintings were always supposed to be for me, and consequently for other people too, but they're my anxieties.

ML: They are the answer to your prayers but an answer to everyone else's in the same breath?

PG: Exactly.

Crate, 2014

oil on paper, 44" x 48"

photograph courtesy of Paul Gagner

ML: I feel like your paintings are white guy jokes. Do you think that's true?

PG: [Laughs] Yeah, well, I'm a white guy. Gender is something interesting, and it’s not lost on me. I grew up in a small town in the Midwest that was not a diverse place whatsoever. I had never been to a city, which was Minneapolis-St. Paul, until I was seventeen or eighteen. I'm a white guy and the paintings are all self-portraiture, so the things that I deal with are being a white male. It’s a place of privilege, which isn't lost on me.

ML: I think of abstraction as the mantle of the white guy, this thing that you're struggling to attain, but it becomes a joke because you just can't.

PG: Yeah, I like to poke and prod. At this point, certain art, certain movements, certain people, have been raised to these heroic positions. Why, exactly?

ML: So do you feel like you are questioning why they have been placed there at the same time as whether you can be placed there?

PG: Well, success is a thing you're asking about in these questions. To me, success, and what I hope to attain with the paintings...well, “I'm not really sure” is the short answer. I think we have a tendency to have a revisionist view on history, and we tend to elevate these very white, masculine figures in a way that's kind of without question. The next generation spends their time knocking them down, and then the generation after that spends their time knocking those people down. I don't have any beef with anyone per se. I guess my interest is demystifying. I had this professor—a good friend of mine back home—who was very adamant that there was no such thing as talent. And he was such a good teacher for that reason. He could teach you to draw and paint from the figure and he was very effective at that. I learned a lot from him. And I started to realize that there's not this magical skill-set. Maybe it comes a little easier for some people. But I'd like to believe you can learn these things, that it’s a matter of being dedicated and focusing on it.

ML: Let's talk about abstraction a little more. There have been a lot of assumptions in the questions that I've asked you. Do you think abstraction and representation, or abstraction and figuration, are at odds? Do you think about that when you're painting?

PG: Yes. I do consciously think about it. They do feel like one side or the other. I don't really think the world is so binary, but on one hand, people do have a way of talking about painting as if it were one or the other. It’s almost like a checklist. "Oh you're a painter! Are you an abstract painter or a figurative painter?" It’s almost like choose your own adventure. It becomes a flow chart. "Oh you're an abstract painter! Is it geometrical abstraction or is it gestural?" And it just becomes a checklist like "Oh I can picture what you make!"

ML: Is this a way of hacking the choose your own adventure? Like you got this far as a figural painter and now you're jumping across to the abstract painter's narrative?

PG: That's a funny way of looking at it. Well, sort of. There are these conversations that happen when I'm making the painting. Should I render this more realistically or less so? Should it fall apart? Should it be more descriptive? Does it need to be? These are conscious decisions. Because I put abstract paintings in the context of a book or a studio, it’s given me the freedom to choose how things are rendered. Is it flat and dumb—the bare minimum of information—or is it highly rendered and three dimensional? It does become like a choose your own adventure. Some of that has become a tool for pushing awkwardness. In one of my paintings, Stoop Sale, there's a railing and a sky or background that just kind of falls apart to something abstract–or who know's what's happening there. There are sky colors I guess.

ML: You're putting abstract techniques into a narrative structure that can't interpret them. It's like the system starts to sputter and breaks down, it just can't make sense of it. Are you trying to do that?

PG: I am definitely trying to do that. I love them occupying the same space. That tension, that awkwardness is really wonderful. Oftentimes it’s treated as a buffet—a little of this, a little of that. I like that you can hack art and just use whatever is necessary, and just throw it onto the painting. I like that it creates this contradiction.

ML: I always read these paintings as the narrative's revenge on the abstract painting, like "I'm just going to put a box around you, and then how powerful are you going to be?"

PG: I really like your take on that. The beauty of painting is its ability to render the impossible. Abstraction is something that is not unique to painting, but with figuration, it’s something that you can exaggerate to any length, any way you want, and I love that ability in it. But what's particularly wonderful about that manipulation is, it’s not that you could go anywhere, to these crazy lengths, or the ends of the earth, to show how malleable it is; it’s more that its controlled. I'm gonna use a Game of Thrones analogy. I love those books. What I like so much about that show is that they hint at

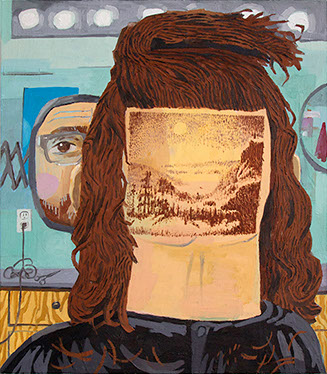

Hairscaping, 2015

oil on canvas, 26" x 30"

photograph courtesy of Paul Gagner

magic, they talk about magic being something real, but they show it so controlled. You see just a little bit of it. And as a viewer, you know that it exists in the show, but because it’s so controlled and because other people doubt it so much, you start to wonder if it actually does exist. That control is what makes it so wonderful. Maybe the only problem in the story is that Bran has opened up these possibilities that seem limitless, and that's where I start to lose interest.

ML: It becomes the Matrix Reloaded.

PG: I don't really give a fuck what's going to happen here because he can go back in time, and I start to shut down.

ML: Has the Bran storyline been fully traced in the books?

PG: I think he's gotten to the three-eyed raven but hasn't actually started having all the visions yet.

ML: The idea of the canon seems to be very important to your work. I'm so glad you brought up Game of Thrones, because that negotiation between the canonical and the non-canonical is unfolding in real time. There are a lot of literary canons, great stories, that end up getting fucked up by people who don't get what's great about the story in the first place. Do you feel like you're the one fucking up the painting canon?

PG: [Laughs] I hope so! Not in an aggressive, antagonistic—well, maybe a little antagonistic, but not like a "bro-y" asshole kind of way. I think of Francis Bacon being a strange hiccup in painting at the time when he was making work. You think of all the things that were happening around him, and he's making those paintings. I don't know if he forced his way in there, but his paintings seem like such an anomaly.

ML: And yet still a part of the story, not disregarded.

PG: Exactly. I've got a lot of respect for that.

ML: I’m going to phrase the next question as a choose your own adventure. Do you want to talk about the bro-painter or do you want to talk about fan fiction?

PG: Let's go with the bro-painter. So, what do you mean by the bro painter?

ML: It refers to a certain class of white male painter who is not...

PG: Self-aware?

ML: Yeah, I guess you could say not aware that there is a world outside the studio, or outside of that privilege not just in birth, but in the favor the art market continues to show them.

PG: Success seems to be a big part of a question like that. Art schools have more women in them than they have males, but more males are being successful, or making more money than women, for some fucking reason, and that's a strange, curious, pretty obviously fucked-up problem that we're presented with. What strikes me is, art is supposed to be self-aware, self-reflective. When did it not become self-reflective? I've certainly seen privilege, sexism and discrimination. I haven't experienced it so much because I'm, fortunately or unfortunately, a part of that privileged gender and race, but I can see it around. It’s apparent, and success is something that comes along with that.

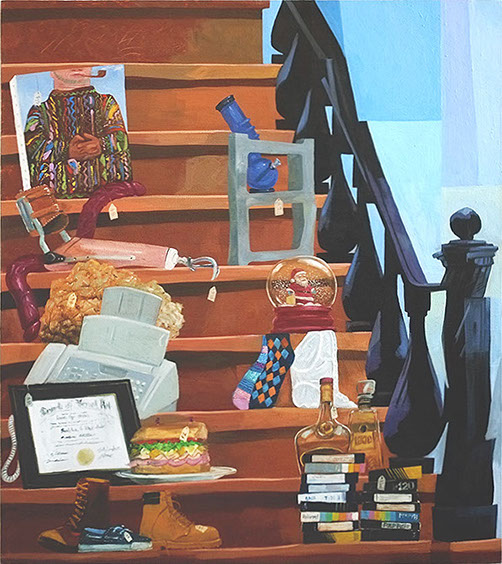

Stoop Sale, 2012

oil on canvas, 44" x 48"

photograph courtesy of Paul Gagner

ML: Do you feel that these are things that you're talking about in your painting?

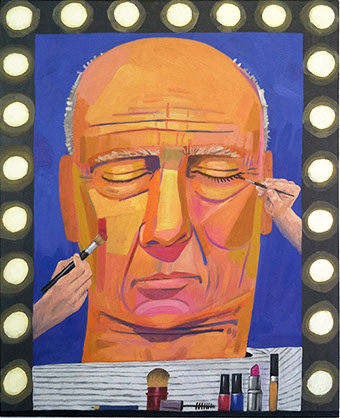

PG: Yeah, sort of. I'm interested in showing how the sausage is made, rendering something unheroic, because the hero is something so silly and dated and irrelevant. When you see Phillip Guston getting a pedicure, there's nothing more—well I wouldn't say it’s unheroic, but I could imagine he probably wouldn't want that. He would feel emasculated. I get pedicures every once in awhile. I actually think it’s really a very pleasant experience. And with Picasso getting a makeover...

ML: What makes the Guston pedicure different from Picasso's Makeover is that, at least in my reading, what I see is Picasso becoming camera-ready, which is kind of receiving the hero treatment. So in revealing that moment, that's a different way of challenging the hero narrative. Do you remember the first Batman movie, the Tim Burton one? When the Joker starts fucking with shit, one of the first things he does is poison the cosmetics supply, so you see the newscasters without makeup.

PG: Yeah! With all kinds of pimples and blemishes.

ML: And it challenges their credibility in a way. You said before that you hope you were lucky enough to be remembered.

PG: I guess a lot of people think about that. I hadn't really considered that, I don't really think about it so much. You know, when it comes to success, which kind of relates back to the bro culture of painting, if there wasn't success to be had, would there be a bro culture around it?

ML: That's a very good question. What do you do with doubt and anxiety? Are they enemies or allies?

PG: At this point allies for sure. They are enemies in the sense that they're not fictional. They are real, and they do hurt, and they do present problems, but they're allies in the sense that I've gotten to a point where I understand how to talk about them, use them, explore them in a way that's mutually beneficial I suppose. I make them sound like they are something outside of me. Like they've got some kind of earpiece "CCHHH—talk about how this is mutually beneficial." You mentioned something about fan fiction?

ML: The non-canonical expansion of a universe. I think about it as an artist, especially right now, when so many people can be accused of lifting an earlier art historical precedent, in the same way some kid would write an unauthorized Star Wars book.

PG: I'd never thought of putting those together, but it’s a really great connection. I don't think of myself that way.

ML: Neither do I, I think that the autobiography is your genre.

PG: Everything here is straight-up autobiography. I suppose there is a kind of self-deprecation that is pretty apparent in the work, which would mean that it would have to do something with me. And I think the books also do a pretty thorough job of hinting at that or suggesting that these are anxieties that...

Pablo's Makeover, 2015

oil on canvas

photograph courtesy of Paul Gagner

ML: They really suggest your need for them, which is I think what makes them so relatable. You take yourself down a few notches as the artist and put yourself, not necessarily on the level of the viewer, but on the level of another artist.

PG: That's good. That's what I was really hoping for. I think most people who have gone through grad school for art can understand the real and the imagined pressure that comes with that. And then afterwards, it takes a little while, but you breathe a heavy sigh of relief. And then you get on with your life.

ML: You have to think about how to rebuild your work after this ruin.

PG: It certainly feels that way.

ML: I was listening to an NPR interview with a biographer of Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis. The biographer was talking about how Brandeis lived in this incredibly austere apartment, decorated only with old prints of classical ruins, contemplating jurisprudence. Such a cliched thing, right? And then I thought, these abstract paintings nested in your work, you're phrasing them like classical ruins. Do you think that's true?

PG: That's a great question. I was born in the mid-seventies and I didn't become a conscious artist until the late-nineties and two-thousands. Abstract expressionism had been gone, not forgotten, but gone for fifty years at that point. So if we talk about artists as always being a generation ahead of the one before it, the one that has been hailed and lifted to this sort of reverence, then I missed that boat by a couple generations. And so, why am I not talking about conceptual art or performance art?

ML: Anselm Kiefer said the ultimate objective of Nazi architecture was to leave impressive ruins. They weren't supposed to exist for very long as functional buildings, but supposed to disintegrate into ruins that would strike future generations with awe. Conceptual art doesn't leave an impressive ruin in the same way that Ab-Ex does.

PG: No it certainly doesn't. Minimalism is impressive, but it dissolves into something intangible, or ethereal. I don't have anything against conceptual art, I think some of it is really great. I have some love for it for sure. But I think for me, abstract expressionism encapsulates a very broad sense of heroic art that art since then doesn't quite capture. It’s not like I chose it for that reason, it just so happened that I loved abstract expressionism as a youngster. But it does do a good job of filling in that space of "Exhibit A: Abstract Expressionism." Maybe it’s a little convenient for a punching bag, like the tortured artist that comes out of that conversation. But I'm a tortured artist. So for someone to knock down that kind of painting, I'm doing that kind of painting too. I'm not Robert Rauschenberg erasing a Willem DeKooning, leaving no evidence of it. The evidence is clear and I'm even more guilty of it than they were.

ML: More guilty of what?

PG: That tortured artistic expression.

Paul Gagner is an artist in Brooklyn, NY. His three person show A Series of Moves is at Driscoll Babcock Project Space through August 12, 2016. He earned an MFA in Painting and Sculpture from CUNY in 2009. His work is featured in New American Paintings no.122, the Northeast edition 2016. Recent exhibitions include Paul Gagner & Christina Tenaglia at Weathervane, Spring Break Art Show, Holiday Show at Lesley Heller, No Irony Here at The Parlour, and Grexit at Centotto.

Michael Levin is an artist in Brooklyn, NY and a contributor to Painting Is Dead. He earned an MFA in Printmaking from Pratt Institute in 2015 and has recently shown at Torrence Shipman Gallery in Jabroni, Jabroni, Jabroni.

A Series of Moves:

Paul Gagner, Karen Lederer, and Rachel Schmidhofer

June 28 – August 12, 2016

Driscoll Babckock Project Space

525 West 25th Street New York, NY

(212) 767-1852

Gallery Hours

Monday-Thursday: 10am - 6pm

Friday: 10am - 5pm

Disclaimer: All views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors, owner, advertisers, other writers or anyone else associated with PAINTING IS DEAD.