Hiba Schahbaz in studio

Photo: Scott Robinson

ML: I’ve heard you speak about the idea of exhausting a figure. What does that mean to you?

HS: You know how artists get obsessed with certain things. I like it when you see an image repeated again and again until one day, it becomes a totally different image. Firstly it’s a compulsion for me to repeat certain figures and to see where I can take a figure. There are certain figures which will be repeated a lot for a few years and then will sort of fade away and then come back in another painting. I suppose I become attached to the figure. I have an emotion or a memory attached, so I keep repeating it –for some more than others. You’ll notice a figure with her hands held up is repeated in several of the tea paintings, and in some of the color paintings too. This figure came from a dream. I was having this really vivid dream where I was standing with my hands up, and I had these socks on my hands. So after I had that dream, I started painting this figure a lot.

ML: A lot of your paintings have a dreamlike sensibility. Are you drawing on dreams intentionally and trying to create a dreamlike sensibility?

HS: Dreams can sometimes affect my emotional state and that does seep into my artwork. Sometimes it has nothing really to do with a dream, but with something I’m experiencing day to day, or with something that’s happening in the world around me. It’s kind of a mixture. When I was younger, I used to keep a sketchbook next to my bed. And every time I would wake up in the middle of the night, I would draw something. I don’t do that anymore. If something lingers, then I’ll make it. Otherwise, I won’t. But there are other repeated images, like the hanging figure, which has been repeated in a lot of works. For some reason I’m really attached to that figure. She would make good graffiti...

ML: So what you are? Are you a miniature painter?

HS: I’m a pain in the ass. And I’m a miniature painter. Miniature painting is this centuries-old art form. I trained at the National College of the Arts in Lahore, and that’s a really old art school. It was founded as the Mayo School of Art, and after the Subcontinent was colonized and India and Pakistan were divided, Pakistan got the National College of Arts.

Tea or Coffee, 2014

Gouache, watercolour, tea and gold leaf on wasli

10" x 12"

photo: Louise Kim

ML: And that had already been a school that had been teaching traditional Indo-Persian crafts?

HS: No, a miniature department was formed within the Fine Art program in the 1980s. Though at that time, students were hesitant to adopt what appeared to be an archaic and obsolete art form. Because of European influences, many Subcontinental artists had adopted Western painting techniques, neglecting their own rich painting culture. So I ended up at the NCA in 1999, 2000 –something like that. Actually I had planned to become an oil painter too, but I found that the temperament and aesthetic of miniature suited my personality better. I kind of just ran with that. And that’s how I fell into it. I didn’t realize that my life would be hell.

ML: Do you have any other artists in your family?

HS: Oh yeah, my dad and my mother both were artists. My mother painted and my dad went to the National College of Arts as well. Then he went to NYU and moved from art to television. He worked for TV all his life as a set designer. When I was a kid, I used to go to the television station and help paint all these sets –like all these Jinnah portraits and all these crazy, ridiculous village scenes and stuff. I used to do that and every time I go around Williamsburg and Bushwick and see all this tagging, its amazing! I really want to do that. I want to start tagging walls.

ML: Your family must have been supportive when you wanted to become an artist.

HS: My dad really wanted me to become a doctor. When I applied to the National College –which was the only college I applied to– he called his friends there and asked them to flunk me! He really did not want me to spend my life struggling as an artist. And when I told him I was going to be a miniaturist, that was really the nail in the coffin for him. He was like, “What rubbish, this obsolete art form, who wants to do that? Be creative if you want to be creative!”

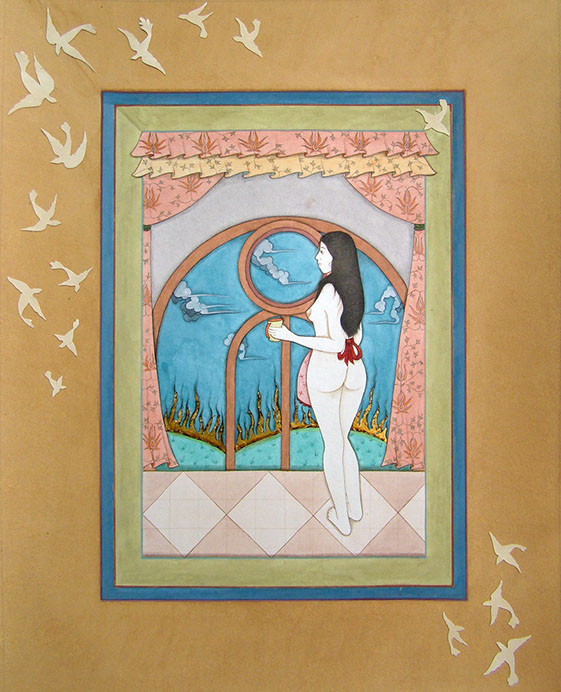

The Guard, 2014

Gouache, watercolor, gold leaf, and collage on wasli

45" x 35"

photo: Louise Kim

ML: Is miniature painting considered a form of kitsch or low art?

HS: No, miniature painting is a very aesthetically evolved art form. The balances you find in traditional miniatures, and the subjects you find… It has been considered a high art, which is why it’s often formulaic. When I think of a trained miniaturist, I think of a trained martial artist. You start training when you are younger and you go through this “wax on, wax off.” It requires a lot of discipline and dedication. When you’re learning how to make a miniature you stop doing everything else and it becomes your focus. Contemporary artists often go out into the world to find inspiration around them and bring that back into their work. But as a miniaturist, you have to go inside, and you have to access a more disciplined and spiritual sort of place, and just be okay with being yourself.

ML: How does that affect content in your paintings?

HS: I found that when I was training, my content was very different from what it is right now. Before, for years, it was just about perfecting a technique. Now I’m okay with making the technique looser, letting myself be in the painting, and using that as a springboard to express myself and put my experiences of the world around me onto the page, which I didn’t allow myself to do when I was training as a miniaturist.

ML: So the history of miniature painting is not one that stresses individual expression as a supreme value and you’ve had difficulty of your own in terms of expressing yourself. Do you think you’re pushing the envelope by using the miniature tradition for self-expression?

HS: I think yes, to a certain degree. Because miniature has been used to document history, to be very objective. I think when I started trying to put myself into the work there was a conflict. I grew up with this whole “miniature is about perfection, everything has to be perfect, you can’t bring your ego into the work” and there I was, trying to put myself into the work. I didn’t even know who I was, so it was this giant bloody mess.

ML: This was a conflict that was happening after you moved to New York?

HS: Yes, because that’s when I started trying to put myself into the work. And this is something I’m still working with. Not just the content, but the fact that I self-censor.

ML: And yet, it’s easy to look at this work and say that it's all personal.

HS: Yeah, because one of the questions I get asked a lot is “Is the work political?” I feel like that was something I used to deny, but the fact is, as an artist from Pakistan –which is a country currently going through a lot of socio-political upheaval– working as a miniaturist, with the tradition of the historical narration of yesterday… Today, it’s used as a means to address so many socio-political issues, women’s issues, and all of those things. It's really impossible to be from that part of the world and not be a

The Hanging, 2013

Tea and gouache on wasli

8" x 10"

Photo: Louise Kim

political artist. Even when the work is personal, it’s still political.

ML: The personal is political.

HS: Yeah, because your entire life is one giant political fucked up mess.

ML: That’s the case for all of us, but only some of us are forced to be conscious of it all the time.

HS: I think that comes from being part of a group of people –when you’re put together with other contemporary miniature painters. Even ten years from now… I know that there are some works which are more political than others, because of certain events that were going on. Last year, there was this series I did called “The Long March,” that was based on this marginalized sect, the Hazara. Their mosques were bombed. They’d been killed for decades and they decided not to bury their dead. And this march started in Pakistan while I was there, so I did a series of works based on that, but I still used my own figure, because I felt like she stood for both things.

ML: So now we’re talking about using your figure to tell stories that aren’t immediately a part of your experience?

HS: Perhaps, yes, but at the same time, watching people die or be persecuted for years is a part of my personal experience, right? And even paintings with women in them… Women is a whole different can of worms where I come from. So sometimes the work is personal but at the same time it’s full of political crap.

.jpg?crc=4070186328)

Untitled, 2014

Goauche,watercolour and pigment on wasli

10" x 12"

photo: Louise Kim

ML: Do you feel free working in your tradition?

HS: Yeah, I mean I realize that my sense of freedom is very different. I’ve tried throwing paint like an abstract expressionist and I’m really bad at throwing paint. I want to be looser and sometimes I accomplish it, like in the recent work I was doing for Sugarlift, “Untitled (Roses)”. That was already an etching and then I was trying to create a lot of movement with paint and watercolors, sort of moving around, and not planning it. That’s something I play with, like going from these extremes of making meticulously planned artwork where I know where every single figure and leaf is going to be, to making artwork which is a little looser, and I just want to go on this journey where I don’t have all the answers, where I’m not in control. Obviously I’m a control freak. Everything is controlled. Look at my eyeliner! So there is a lot of control and that is who I am. It’s important to me. I’m invested in the fact that the painting has to be beautiful, that if a painting is ugly, it just shouldn’t exist.

ML: That sounds like an unpopular opinion.

HS: Not in this studio.

ML: What was your work like before you moved to New York?

HS: There was a lot of copy work originally. After that, all the figures I painted didn’t have faces for social and religious reasons.

ML: Although that seems so at odds with the history of miniature painting, right? Is that the way that it’s taught at the National College, that you don’t do it, or did you choose that?

HS: I think it just sort of happened. I had this paranoia about making faces. But in miniature, you’ll notice that nothing is ever realistic, because it’s about not competing with God.

ML: It’s not meant to be a simulacrum. So you went from not painting faces at all because of a tradition of not fully representing human beings, and now almost all your works involve female nudes.

HS: I’ve always worked with the nude body. I’ve been drawing myself nude since I was a teenager, though my mother hates that. But my nudes were faceless back then. I always thought of it as plausible deniability.

ML: I’ve often wondered whether the figures in your painting are meant to represent you and a story about you or whether you are basically using your own body as a way to kind of construct a figure.

HS: I feel it’s a mixture a both. The figure I use is often a self portrait and is sometimes used to unfold a personal narrative and at other times to ponder a thought or pose a question. Obviously I use myself. And I wanted to use my family and friends but they would never speak to me again.

ML: You have some works with your family members in them, don’t you?

HS: Yes, but they’re all clothed. There’s Lost in Greenpoint which is a portrait of my brother, and there’s a portrait of my mom and dad in there, too. When I started attending Pratt, I was making a lot of faceless figures, and at that point I was so disassociated with everything, with

_digital%20pigment%20print_16%20x%2012%20in_2014.jpg?crc=3992432714)

Untitled (Portrait), 2014

Digital pigment print

12" x 16"

myself and the world around me, and everyone kept telling me, “your work is so cold, you’re so cold, could you just chill the fuck out?” A lot of the works were black and white, and I hadn’t painted in color in a long time. The first one I made when I got here was a portrait of Kiki (she’s a model at Pratt), naked on a subway station. This was using a technique called sia qalam, where you apply layers of very transparent black paint to white paper. It took me months and then when it was done, everyone was like, “is this a pencil drawing?” So I thought about what everyone was saying, because the world can’t be wrong…

ML: Do you really believe that?

HS: Yeah, I really do. So I thought about this and I think I tried to start putting myself into my work. Self-expression has always been sort of a problem for me, so I started the process by making a self-portrait in which I was gagged, and this ended up resulting in dozens of self portraits. That’s when I reintroduced color into my work.

ML: How did you arrive at your palette? It seems so consistent across much of your work.

HS: I think it’s personal preference. Though I’m sure the balancing of the colors and the harmony they create is a result of my traditional training. Because I mix my own paints and use a lot of tea in my work, I tend to mix the same colors repeatedly. So the colors are personal, and sometimes I dislike a lot of them. There are times when I make a painting and I’m like, “what the hell just happened?” and I’ll try to go back in and change the color. In a miniature it’s hard to make changes because when you are using opaque washes you can’t layer too many, because you don’t want them to crack. So you have to sort of go in knowing what you want to put down, knowing that if you put something down which is not perfect, you can’t make it perfect later.

Untitled, 2013

Tea and gouache on wasli

8" x 10"

photo: Louise Kim

ML: There’s a low threshold for… for what I’m resisting calling mistakes.

HS: Yeah, and also because the sheets I work on are handmade, you don’t want to erase them and you don’t want to have to pick the paint off. You can remove the paint with water, but you’re gonna disturb the surface. As a miniaturist, when you are trying to make everything look flat and perfect, having a disturbed surface and working with a really fine brush on it is not conducive to making a perfect painting… I have noticed that these are the kind of things which, whereas someone else would look at it and think it’s so perfect, as a miniaturist it’s like “no!” I’ve always struggled with this desire to make everything technically perfect. In these works, I’ve tried to let that go. When I look at them, I see the imperfections, and I’m struggling with them, on a daily basis, wanting to go in and work on them and make everything look perfect. And someone else will walk in and say, “oh my God, it is so smooth,” and my mother will call and she’ll say “what on earth is that? You used to make such beautiful paintings...every single hair strand.” And I’ll say, “Mom, I just can’t spend that long working on a painting anymore.”

ML: Not to mention that miniature painting developed with many people working on the same painting together in a workshop. What is it like to be a miniaturist where you are the only one working on your paintings?

HS: It’s all I’ve known. When we were trained as miniaturists, we were trained as solo artists. So we didn’t really have the karkhana –or workshop– to fall back on. I guess what happens with the solo process is that you become more connected to the painting, but that’s where the artist’s ego also comes in, because it’s your painting. It’s a lot of work.

ML: New York definitely puts production demands on artists. How do you navigate those demands with a way of making work that is so time consuming?

HS: I try to work with people who understand the work, and who understand that I can work 70 hours a week and not produce as much as another artist working seven hours a week. I like to work with people who appreciate the artwork as much as I do.

American Beauty, 2014

Goauche,watercolour and pigment on wasli

10" x 12"

photo: Louise Kim

ML: Are these gallerists you are talking about?

HS: I’ve found that the art world is filled with a lot of diverse people, gallerists, curators, writers and other artists who seem interested in my work. For instance, there is a gentleman I work with in Italy. He has a really great space there, and he shows a lot of contemporary art, a lot of video and performance-based art. But when he engages with a miniature, he looks at it differently. He can do the mental switch between other artwork and a miniature painting. He does not expect everything to look the same. That is really important to me, because it doesn’t disturb my process. I know this work is going somewhere, and the worst thing that could happen is to not figure out where. I need to feel okay with the process, and I need to come to terms with where it’s moving. And I know it’s slow as dirt.

ML: I notice there are collage elements in some of the new works. Is that a concession to time?

HS: Collage has always been really interesting to me, probably because when I was in undergrad, I used to skip all the collage classes in the drawing class. I hated sticking stuff. But I’ve always been interested in having layers. A lot of making a miniature is about building up layers within a painting. There is your under-layer, and you build up washes slowly, if you want more transparent washes. Sometimes what looks like just one layer of tea is actually 20 layers, and that creates a softness in a painting. I guess collage was sort of the next step to that layering process. It’s something that I got into that I definitely do want to explore more, but it’s such a new thing for me that I’m still sort of navigating it. But yeah, you can go to a restaurant, wait for your lunch, and sit there cutting shit, making a mess, everyone hating you. It works.

My Selves, 2012

triptych with 21" x 27" pieces

Gouache, watercolour, gold leaf, tea, and collage on wasli

photo: Louise Kim

Hiba Schahbaz lives and works in Brooklyn, NY

Michael Levin is an MFA candidate in the Printmaking department at Pratt Institute

Disclaimer: All views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors, owner, advertisers, other writers or anyone else associated with PAINTING IS DEAD.