Tullio Crali

Before the Parachute Opens (Prima che si apra il paracadute), 1939

Oil on panel, 141 x 151 cm

Casa Cavazzini, Museo d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Udine, Italy

Photo: Claudio Marcon

Futurism at the Guggenheim

“There is not a document of civilization that is not a document of barbarism.”

-Walter Benjamin

This is not a new account of Futurist history.

There’s a common assumption that art is or represents the zenith of humanity’s highest cultural aspirations, values, and fulfillment. Art and culture are believed to be inherently good for people, and the more the better. Simone Weil wrote, “Art is the symbol of the two noblest human efforts: to construct and to refrain from destruction.” If you think about the history of art for more than a few minutes it’s easy to start picking out counterfactuals: a sculpture by Richard Serra killed a worker installing it at the Walker Art Center in 1971; Tom Otterness shot a dog to death in a film piece he made in 1977; one of Christo’s umbrellas crushed a woman in California in 1991; in 2007, the Costa Rican artist Guillermo Vargas Jiménez ostensibly presented a starving stray dog as an installation piece at a show in Nicaragua and later got booted from the Spanish Bienal de Pontevedra when he attended the opening reception wearing a t-shirt that advocated for a Basque terrorist organization; the New Museum semi-notoriously required visitors to sign liability waivers for participation in Carsten Höller’s 2011 retrospective, “Experience,” which included several interactive artworks resembling playground equipment, deemed a potential threat to public safety; that same year, Marina Abramovic exploitatively used mute and nude performers as table decorations at an indulgent LA Museum of Contemporary Art fundraiser. The list goes on.

Viewers, workers, artists, and studio assistants have been degraded, maimed, injured, or killed in numerous notable incidents. And perhaps more fundamentally, much of art’s history is a catalogue of objects designed to affirm the power, ideologies, and influence of the rich upon the disenfranchised, a problem identified by several scholars, and especially effectively by John Berger. Many of those examples weren’t intended to harm or provoke. Rather, they were accidents, or they resulted from historical biases or misconceptions and perhaps don’t damper the regard of art as a force for goodness and the spiritual, political, or emotional benefit of humanity.1

Installation view: Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 21–September 1, 2014.

Photo: Kris McKay © SRGF

A particularly clear, affirmative example of the potential for art to be inhumane, degrading, and non-transcendental stands above those instances in its active, eager insistence in falsifying art’s conventionally lofty rhetorical billow. Futurism, now celebrated in a large survey at the Guggenheim, was at least in part aimed at cleaving the world, advocating for destruction and violence, and explicitly encouraging dehumanization, mostly through beautiful paintings, prose and poetry, and sculpture. “Italian Futurism, 1909 – 1944: Reconstructing the Universe” professes, via earnest didactics, that it confronts Futurism’s contradictions, and it does mention them. The exhibition does not give an argument as to what we should do with such art, or how we might incorporate it into assumptions about art’s purpose and role in culture. Is Futurism an outlier, or is it an indication of a larger problem with our attitude towards art in itself?

In 1909, the poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Futurism’s patriarch, published the first of several manifestos that attempted to define the goals and ideas of his new avant-garde. These creeds changed over time, but the dogma of the group never departed much from Marinetti’s declarations. He seems to have been revered as its figurehead until his death in 1944, and Futurism’s ideological backbone appears to have become more rigid and narrow as time went on. In his first manifesto, Marinetti proclaimed:

We want to glorify war—the only cure for the world—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill, and contempt for woman.

We want to demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice.

These are not the democratic, liberal values that art is expected to embrace.

Less than two decades earlier, Oscar Wilde wrote, “Art is individualism, and individualism is a disturbing and disintegrating force. There lies its immense value. For what it seeks is to disturb monotony of type, slavery of custom, tyranny of habit, and the reduction of man to the level of a machine.” Marinetti shouted an opposing argument and bloodied his teeth in the necks of those exalted pretenses. In the manifesto, he describes a night of revelry, calling drunkenly to his friends, "Let us go! At last Mythology and the mystic cult of the ideal have been left behind.” Marinetti wanted an art that would first be tasked with heralding a new era. That was its highest ethical and political priority. His call to arms is filled with inconsistencies and over-the-top blasphemies, but he was no less serious in his intent to employ art in an eschatological campaign of destroying the old world and inaugurating the next one.

Luigi Russolo

“The Art of Noises: Futurist Manifesto” (“L’arte dei rumori: Manifesto futurista”)

Leaflet (Milan: Direzione del Movimento Futurista, 1913), 29.2 x 23 cm

Wolfsoniana - Fondazione regionale per la Cultura e lo Spettacolo, Genoa

By permission of heirs of the artist

Photo: Courtesy Wolfsoniana - Fondazione regionale per la Cultura e lo Spettacolo, Genoa

One of the most important accomplishments of the Futurists was their prescience about the topography of new world they were demanding. They aimed to create a novel culture and were in step with the emergent social reorganizations that would happen during the subsequent years of the 20th century.2 They demanded war and the destruction of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which had encroached on Italian territories, put pressure on its government, and competed in trade. Within five years of Marinetti’s first manifesto, Serbia’s irredentist Black Hand terrorists assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, an attack intended to repel the Austro-Hungarian Empire from Yugoslavia. It ushered in the most horrific war the world had seen to that point, with mechanized brutality that would result in tens of thousands of casualties every day, over and over and over for more than four years.3 Its effects have haunted us for a century. Within nine years of Marinetti’s manifesto, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was in the process of being dissolved.

And the poetic employment of conflict that Marinetti invokes in his writing, and that was used in the art of the movement, tracks with the increasing importance of brutality as a symbolic tool, even as rates of violence worldwide have decreased during the 20th and 21st centuries. It would seem that specific numbers of casualties in wars like those in Gaza, Syria, and Mexico, which are horrifically large, often matter less to the perpetrators than the perceptibility of the signal the violence is intended to send. Likewise, Guglielmo “Tato” Sansoni’s 1930 painting Flying over the Coliseum in a Spiral (Spiraling), in which a bi-wing plane soars over the crater-like Roman Coliseum, probably looked as majestic and terrifying as we imagine the unseen drones now occupying airspace around the globe.

Futurist architects such as Antonio Sant’Elia, Mario Chiattone, and Alberto Sartori, like many of their peers, designed massive, utopic buildings. They waved the same banner as Le Corbusier, who proclaimed that homes are “machines for living in.” Their plans were subsequently echoed in the state architecture of totalitarian governments in Italy, Germany, and the USSR, as well as the modernist bureaucratic architecture of state edifices in liberal democracies such as the United States and elsewhere. Now the drafts of their unexecuted buildings resemble museums, shopping malls, airports, stadiums, cruise ships, prisons, and resorts—centers of cultural order, leisure, and commerce that require the easy and effortless movement of people in a systematic manner. Corkscrewing through the exhibition, the architecture of the Guggenheim itself feels more and more like a Futurist ode to mechanization, power, and speed designed to persuade the viewer of the finality of its technocratic synthesis of aesthetics and consumption.

The numerous leaflets, books, magazines, and posters on display, all proclaiming Futurism’s supremacy, prefigure the aestheticized and direct propaganda campaigns of the 20th century, which have effectively trickled down into popular media. Like Marinetti, every man, woman, and child in the developed world is now capable of becoming a brand unto themselves, is even encouraged to pursue this as a hobby and possible business model. Some of the best and most radical work in the exhibition is textual, design-focused. Marinetti, astute propagandist and public relations innovator, celebrated the proliferation and inexpensiveness of publishing. Now, using a similar model, writing often forges a home in protected, monocultural habitats, in which every essay can be read as a manifesto: Time Magazine being a manifesto for hegemonic order, The Guardian as left-of-center neo-liberal manifesto, The New American as another right wing manifesto, and Revolution as its Maoist counterpart, Rolling Stone and the like as types of lifestyle manifestoes.

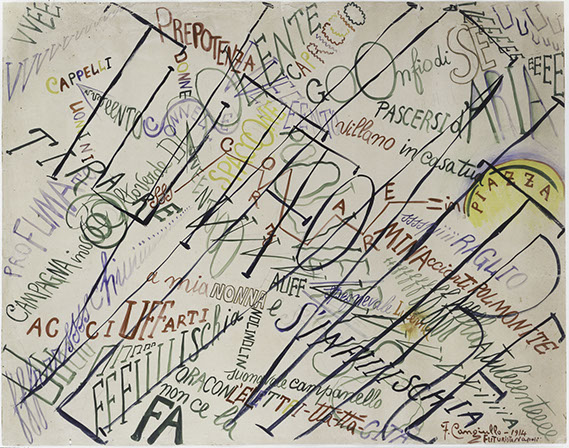

Francesco Cangiullo

Large Crowd in the Piazza del Popolo (Grande folla in Piazza del Popolo), 1914

Watercolor, gouache, and pencil on paper, 58 x 74 cm

Private collection

© 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

The Museum draws few distinctions between the Futurists’ proclamations, paintings, state commissions, and Campari advertisements. (The artists themselves probably drew few distinctions between their commercial and fine art work.) Their desire to erase the discrimination between high and low cultural production was essentially achieved, though perhaps not on the terms that they had anticipated: art is still nominally held to be some kind of apotheosis of human imagination and labor. But commercial production has both elevated the status of work previously excluded from the arts (advertising, design, fashion, etc.) and has repurposed fine art to encourage consumption.4 Indeed, visiting a museum such as the Guggenheim is an activity largely indistinguishable with a trip to a shopping center or boutique. Visitors parade their assimilation of cultural expectations of taste via the visible and promoted consumption of branded signifiers. A selfie that advertises one’s discrimination in terms of dress and style bears so much resemblance to the selfie taken before Gerardo Dottori’s Aerial Battle Over the Gulf of Naples (1942) that they perhaps should be considered as entirely equivalent.

Many of the Futurists’ paintings share congruencies with the experimental photography of their contemporaries, such as Étienne-Jules Marey and Eadward Muybridge. The depictions of movement in those montages gracefully echo Marinetti’s lusty praise for “the beauty of speed.” Such technical images would soon be used by industry to maximize worker productivity and efficiency, to further the mechanization of labor

Filippo Masoero

Descending over Saint Peter (Scendendo su San Pietro), ca. 1927–37 (possibly 1930–33)

Gelatin silver print, 24 x 31.5 cm

Touring Club Italiano Archive

and the human body’s effective synthesis with the factory. The study of “human factors and ergonomics,” or the economical marriage of human and machine, began in the late 19th century, but exploded in the early 20th, just as Futurism was born.

Marinetti’s first manifesto declares: “A roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.” Two years after that was published, distributed, dumped on the streets from high vantages, Rolls-Royce Motors unveiled its iconic hood ornament, called “The Spirit of Ecstasy.” The small metal sculpture shows a woman leaning forward, her large dress catching the wind over her arms so that it extends as two wings. It bears an uncanny resemblance to The Winged Victory of Samothrace, the goddess of victorious warriors. And in the years to come, new mechanical inventions would first shock as cars, airplanes, machine guns, radio, mass production, and moving pictures spread almost instantly at the outbreak of war, and then integrated virtually seamlessly into the world during peacetime: as sedans, jetliners, a middle class manufacturing labor force, telephonic and televisual communications, and leisure entertainments.

Ivo Pannaggi

Speeding Train (Treno in corsa), 1922

Oil on canvas, 100 x 120 cm

Fondazione Carima–Museo Palazzo Ricci, Macerata, Italy

Photo: Courtesy Fondazione Cassa di risparmio della Provincia di Macerata

To contemporaries such as Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia, all this machine fetishism was insane. But long after the distress of their proliferation has worn off, machines and their association with erotic mania now look less like Picabia’s serious jokes and more like standard operating procedure. What were once extensions of mankind’s physical capabilities soon become integrated functions of our thoughts and desires. We are drill presses, automobiles, smartphones, amplifiers, online shopping, and so on.

In all of this, speed, as predicted by Marinetti, was a significant driving force. As asserted by cultural theorist Paul Virilio, the modern era has as its defining feature the foreshortening of physical distance by the immense speeds at which humans, messages, and projectiles can now be made to travel. The scholar and writer McKenzie Wark, differing somewhat with Virilio, claims that the synchronization of speeds and the ability to quickly accelerate or decelerate (as in one of Marinetti’s sports cars, or in the communications of computers with one another, or the deployment of soldiers on a battlefield) is the essential feature of modernity.

Some of the Futurists’ most radical works test these hypotheses. The serate performances that Marinetti and his colleagues held were promotional events and provocations.5 Several different performances would occur simultaneously: loud and dissonant noise music at the same time as an absurd play at the same time as an exhibition of new sculpture and paintings at the same time as the recitation of a fresh manifesto. One can first see in the serate performances an adoration of the flâneur described by Baudelaire, experiencing the array of activities happening on the streets of any modern metropolis, or the worker’s experience of the noise, class divisions, and diverse, simultaneous activities in and around a factory. But we might now also think first of the roiling mass of any multimedia, cross-platform interaction—the collusion of various sensations in any organized space, such as walking down the street, listening to music, and receiving an email. Or there are the varied activities engaged simultaneously online, even among one’s sprawling browser tabs, let along the vast sea of people engaging with the Internet or a city street at any given time, places both physical and digital that comingle and interpenetrate. The new demands for action to be performed in concert at great speed (whether walking across a busy avenue, assembling a new car, or going to watch a movie) have probably radically altered the way we perceive and interact with the world of objects, with individuals and groups, and with ourselves.6 In response, we have been molded to fit the expectations of this new, fast, and synchronized world, just as the Futurists desired.

The Guggenheim notes repeatedly that although the movement praised the future, praised new technological innovations, they also clung to traditional means of representation: oil painting, bronze and plaster sculptures, drawing, and theater. Their use of photography was late and limited. They rarely used film.7 Except for collaged bits of newspaper in Carlo Carrà’s Interventionist Demonstration (1914), as well as the aforementioned advertisements and paintings of burlesques and airplanes, their adoration for popular culture didn’t actually incorporate elements of the novelties, exotica, or inexpensive manufactured goods that were increasingly available in the developed world. Instead, they laced mankind and art with the production of goods and the machines required for them. This might have been different had they received the recognition they demanded from Italy’s fascist government in the movement’s later years. Their relationship with Mussolini was tenuous, with occasional protests from Marinetti concerning anti-Semitism, Hitler’s denigrations of Modern art, the Fascist Party’s support for pre-existing institutions and the Catholic Church. And art remains no different today, having to kiss and scorn the hands that simultaneously feed and abuse it.

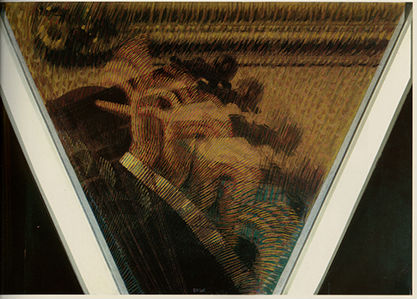

This is not to say that the Futurists didn’t prize art and make beautiful heaps of it. Many of their more famous works appear now to be regional derivatives of Cubism, Neo-Impressionism, Synchromism, and other forms of early 20th-century abstraction—showing Futurism’s indistinct separation from other avant-garde movements of the time.8 But there are numerous beautiful works on view. Giacomo Balla’s The Hand of the Violinist (1912) depicts the

Giacomo Balla

The Hand of the Violinist (The Rhythms of the Bow) (La mano del violinista [I ritmi dell’archetto]), 1912

Oil on canvas, 56 x 78.3 cm

Estorick Collection, London

© 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

movement of a musician’s hand on the neck of his instrument with superimposed images made of radiating, vibrating lines of color. It is technically stunning, and is painted on a bizarre, trapezoidal canvas that seems far ahead of its time. Umberto Boccioni’s The City Rises (1910-11) is likewise constructed of small, energetic marks, here depicting dawn over Milan. Workers toil in the foreground, leading horses through a bustling space. In the background, factories rise into the breaking sunlight. An early work by Carlo Carrà also captures the fervor of the burgeoning Futurist movement with similar stylistic conventions. His large painting The Funeral of the Anarchist Galli (1910-11) shows a riot that ensued during the burial procession for the anarchist agitator Angelo Galli, who was killed by police during a workers’ strike six years earlier. It emphasizes another point of ambivalence in Futurism’s simultaneous embrace of anarchism and more chauvinist, nationalist, militaristic, and finally fascist tendencies.9 All of these paintings represent some of Futurism’s greatest treasures.

Umberto Boccioni

Unique Forms of Continuity in Space

(Forme uniche della continuità nello spazio), 1913 (cast 1949)

Bronze, 121.3 x 88.9 x 40 cm

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,

Bequest of Lydia Winston Malbin, 1989

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Image Source: Art Resource, New York

It’s difficult to imagine how threatening the paintings on display once were. Futurism didn’t cause these developments—it advocated for them. No one could have predicted precisely how the radical changes of the 20th century would affect socio-cultural relations, or vice-versa. For all the talk of the rapid rate of technological advancement in the past few decades, one might see the fin-de-siècle as far more radical: the move from telephony to fax, to email, to SMS, may appear incremental if compared to the birth of flight, to the invention of recorded sound, to the very first moving images, to the original mechanized war, which erupted 100 years ago.

In the intervening century life spans have nearly doubled, hundreds of millions of people have been lifted out of poverty, and despite two global conflagrations and multiple genocides, rates of violence have been declining.

The market for art has expanded enormously, encouraging a flood of images that partake in the economy of the image, cavorting with and competing against theme parks, religious and educational institutions, sex shops, superhero movies, tapas, 401ks, self-help webinars, in-vitro fertilization clinics, and any other promise of fulfillment. One can imagine that the Futurists would be very pleased with the developed world as it is now constituted: a hegemonic order of neo-liberal freedom, where individuality is encouraged insofar as that individuality is expressed via the participatory consumption of products and images generated, distributed, perpetuated by capital.10 Art is only one tool in this consumer dystopia, presented as both the apogee of culture and one set of products among an infinite array from which consumers may choose to constitute themselves. As with all those other products (which compete for the discerning shopper’s attention) art is prized for its discrete peculiarity, its novelty, its packageability. So then how do we earnestly make claims for art’s universal, or even near-universal, goodness and beneficence? Art can be used to propagandize for the most horrific or mundane injustices we can see, and is often studied to get a better understanding of the psychic impacts of the injustices of the past.

Because the Futurists look like history’s losers—their movement and their rhetoric essentially destroyed by the close of the Second World War and by Marinetti’s death—it is easier to hold their program away as a formalist experiment with an unpalatable footnote of anti-liberal vulgarity. But that their aims have been smoothly integrated into the contemporary world denudes the lie. This is art; this is culture. They are as much records of inhumanity as they are gifts.

1 For what it’s worth, I think it’s a pretty sure bet that more people have been materially harmed or killed by artworks and art materials than have been physically helped or preserved by them.

2 Part of this might be attributable to their ability to see technological progress outside of Italy, which already far exceeded the changes happening within the nation’s borders.

3 A few Futurists—the painter Umberto Boccioni and the architect Antonio Sant’Elia—died during the war; Gino Severini abandoned the movement and returned to painting naturalistic images shortly after the war’s conclusion. War continued to be a guiding image for Futurism though and, true to principle, Marinetti volunteered for service on the Eastern Front during World War II, despite being over 60 years old.

4 The details of this integration could, probably do, form the basis of several books. But, for example see Andy Warhol, recent exhibitions of fashion at various art museums, the high regard for Super Bowl ads as an art form, and the appropriation of several famous paintings by Volkswagen over the years.

5 Little recorded documentation of these events seems to have survived, but the museum provides a video with a few short clips, close-captioned narration, and caricatures of the manic happenings.

6 This is not an argument about the possible loss of individualism or the atomization of society. Synchrony and speed need both differentiation of things and the collectivity of action.

7 Excerpts of the one surviving Futurist film (Thaïs, made by Anton Giulio Bragaglia in 1917) are on view, and they are beautiful.

8 It perhaps bears mentioning that Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912) was presented first as nominally Cubist, then as a Futurist painting. Kazimir Malevich, a few years later, declared the terminus of art in his movement, which he first named Cubo-Futurism before settling on Suprematism. It was also only vaguely distinct from Constructivism and Concrete art.

9 It’s worth asking whether these contradictions only appear as such now, after these political and aesthetic camps have fully gelled and completely fractured?

10 Individuality outside those boundaries is severely restricted, and individuality within those boundaries, as noted by Wilde and Marxist critics such as Terry Eagleton, is of a type where people are individual as much as they are singular, interchangeable units.

From the webstie:

February 21–September 1, 2014

The first comprehensive overview of Italian Futurism to be presented in the United States, this multidisciplinary exhibition examines the historical sweep of the movement from its inception with F. T. Marinetti’s Futurist manifesto in 1909 through its demise at the end of World War II. Presenting over 300 works executed between 1909 and 1944, the chronological exhibition encompasses not only painting and sculpture, but also architecture, design, ceramics, fashion, film, photography, advertising, free-form poetry, publications, music, theater, and performance. To convey the myriad artistic languages employed by the Futurists as they evolved over a 35-year period, the exhibition integrates multiple disciplines in each section. Italian Futurism, 1909–1944 is organized by Vivien Greene, Senior Curator, 19th- and Early 20th-Century Art, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. In addition, a distinguished international advisory committee has been assembled to provide expertise and guidance.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

1071 Fifth Avenue

(at 89th Street)

New York, NY 10128-0173

Disclaimer: All views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors, owner, advertisers, other writers or anyone else associated with PAINTING IS DEAD.