Exaggerated Perspective: Some Thoughts on Wayne White

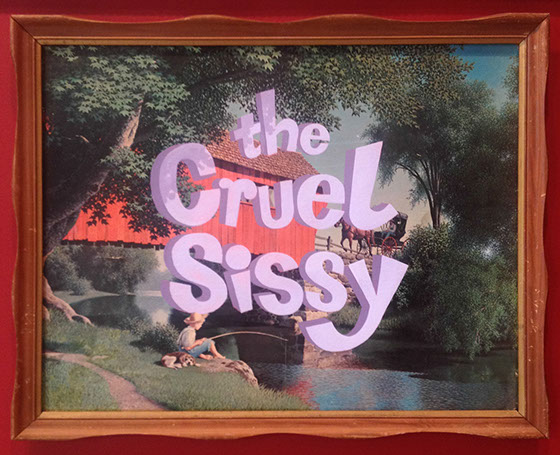

Entering the gallery, there are two adjacent walls of landscape paintings filled with three-dimensional text. Eye-catching phrases invade serene pastoral images: a thrift store lithograph featuring a straw-hatted youth à la Huckleberry Finn is unknowingly introduced as "The Cruel Sissy"; the short phrase "Is too" stands at odds on opposite banks of a river from “Is not”, and a young rural couple's quiet moment together is boldly interrupted by the blunt word "TURD" hovering just over their heads. As you move further in, a wall of loose watercolor drawings leads to the back of the gallery, where you are ambushed by monsters. Two enormous red-suited, sinister-faced musicians grin and engulf you with exaggerated perspective. These giant marionettes, caricatures of 50's country-folk musicians The Louvin Brothers, may only sway slightly as they are suspended in the gallery’s recycling air, but they seem to fly at you, wings spread, as they play their cardboard instruments as loud as hell. As you gaze at them, the black button eyes of Charlie Louvin stare right back and as you consider this fascinating monstrosity you can’t help but wonder, “Why The Louvin Brothers?” You glance up to see the belt buckle of Ira Louvin, which reads simply: “F.U.” Oh, that is probably why.

Sarge

Cardboard, wood, acrylic

2014

60 x 30 x 44 inches

The film is a genuinely enjoyable biopic about White’s artistically formative years continuing through the success of the book; the leitmotif attached to White in the documentary is that of an artist whose primary motivation is to bring comedy into a stuffy, inaccessible art world. As it turns out, this has become the way people perceive his work across the board. Unfortunately, while that is a great hook for a two-hour documentary, it has, as White has himself noted 1, put the artist before the art.

You are in Wayne White’s world. His most recent exhibition at Joshua Liner gallery ran through October 11th but this show has been only the most recent spectacle in what has been a whirlwind of increased fame since his monograph, Maybe Now I'll Get The Respect I So Richly Deserve (2009) hit bookshelves nationwide and made good on the title's promise, increasing his sales and introducing him to the world as a charismatic painter of words. The book directly led to Neil Berkley’s 2102 documentary about White titled Beauty is Embarrassing which, partly due to the nature of the medium and its availability for download, has continued to increase White’s fan base exponentially. But the documentary, unlike the book, has a side effect that was most likely unintended.

I recently attended a screening of Beauty is Embarrassing that was followed by a Q&A session with White and Todd Oldham (designer/ Wayne White-champion), moderated by art and comedy critic Miriam Katz. Though I had at first hoped to ask a question of my own, I became almost relieved that Katz conducted the Q&A more as an interview; it's difficult to ask even a question as unpretentious as "how do you feel the preexisting landscapes are altered by the addition of your text?" or just "can you talk a little about the relationship between your text and puppets?" when in opening of the documentary, the artist himself mocks common 'artspeak' in defense of entertainment:

"Entertainment is a dirty word in the art world. You’re not supposed to ‘entertain people’; you’re supposed to make them question their core values and make them reevaluate their lives and give them a deep insight into blah-blah-blah-blah-blah-blah-fucking-blah."

There's really not much to ask about his art's relation to art history after that. In fact, White manages to also get in a denunciation of his comparison to Ed Ruscha - the most obvious big name artist to whose work ArtForum enthusiasts could compare White’s word paintings.

I’ve been following White’s work for years now, and although I have enjoyed the documentary since it was first released, I had never before noticed how dramatically it differs from the experience of viewing his work. Sitting and contemplating his paintings and sculptures, like all good art, is an experience that rewards the time invested; nuances in the interplay of language, image, and composition open to reveal hidden gems. The art itself doesn’t fully support the “man on a mission to entertain” depicted in the documentary,

and this is mostly highlighted by the content of the work—which is not to say that entertainment can’t have content, but often White’s choices clearly do not have comedy or entertainment at the forefront.

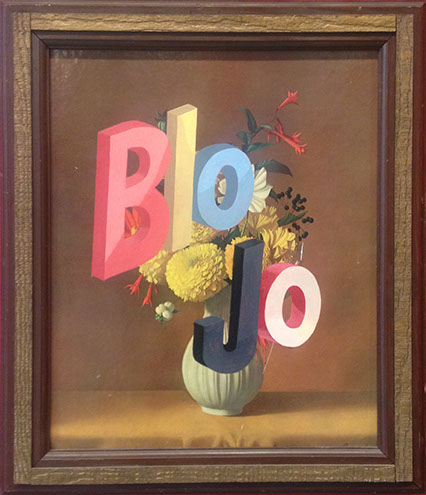

That being said, genuine comedy ("real funny, not art world funny" as White has put it 2) is present, as always, in the current exhibition—I'd be embarrassed to admit how long it took me to fathom what a bouquet of flowers with the phrase "Blo Jo" meant, but when it hit me, it me hard—but the humor in White’s work is merely a red carpet. It is an ostentatious way of inviting us into a world dreamed up by someone who is a feverous creator, an intense observer and a natural poet. He is an artist whose voice is clear. The paintings, in the sense of paint-handling, are all treated in the same manner: tightly drawn, well conceived, carefully planned and underpainted, but the effect of each one is quite different. This is where you can see that the technique has become a comfortable place for the artist to speak frankly: the paintings open up to us as small insights into the artist’s perspective of the world.

Blo Jo

2014

Acrylic on offset lithograph

23 x 19 inches

The piece that gives the show its name, for example, contains a phrase that White has revisited a couple of times. The painting, Invisible Ruler, at Liner Gallery is small, 31 inches wide, and features a road along a riverbank with what appears to be a shepherd and his flock walking in the distance. To the right of the composition are the words, which come at us in a rigid line of block letters. The text is all white but reflects the autumnal colors in the scene into which it has been painted. The words recede into the background until the leading "I" is just about to dip into the river. The phrase, “invisible ruler”, is clearly a reference to the object one could purchase at an office supply store, but has been taken out of context and repurposed here to highlight the oddity that underlies these seemingly innocuous words. By doing so, he presents and equalizes the various interpretations of the term—hidden puppeteer or an unseen measuring device? It is a great piece, the equal of any other in the show, and I am particularly enamored of the fact that it is has been evoked as the show’s title, for one major reason: it's not funny.

As a painting, Invisible Ruler is overtly poetic; the choices made are romantically driven. It is when White makes a picture like this that you can start to see its qualities sprinkled throughout the show, from the little bits of self-criticism, like the phrase "I started a joke" carved from sponges, to the contemplatively minimal word "LOW" carved from ancient stone and catching the setting sun of a rocky beach, and back to the enjoyably frustrating phrase "instgrat", but Invisible Ruler also nicely brings the content back around as a contrast to the Louvin Brother Puppets at the back of the gallery, all covered in red with custom flames on their sleeves and pant legs. (Oh, and the actual Louvin Brothers had a popular album/song called Satan is Real, the cover of which featured a giant cut-out devil behind some staged hellfire, which is probably worth noting.)

The Cruel Sissy

2014

Acrylic on offset lithograph

24 x 30.5 inches

There are actually a couple of other cardboard constructions in the show: a few severed heads. These, along with some of the drawings, are artifacts from his Civil War installation FOE that was created for a residency at York College in Pennsylvania earlier this year and—not that the Civil War isn’t hilarious subject matter—are perfect examples of work that is not entertainment-focused. The sculptures, titled Sarge, Blue Reb, and Shackface Mooneye portraying (respectively) a Confederate Soldier, a Union Soldier and what I am going to interpret as a civilian, are fascinating and elaborately rendered, particularly Shackface and Sarge. The former is aptly named, a blocky, slack-jawed rustic with face made of clapboards and an eye that floats like the moon through a windowpane. Sarge has similar qualities, but takes them in a different direction: his anatomy is more disjointed and the structure of it smacks of something familiar. Typically you'd be hard-pressed to find any other artists that could be taken as Wayne White’s influences, but it is hard to look at this head and not think of Picasso, specifically the costumes he created for the 1917 ballet Parade. In spite of White’s 2012 painting which eponymously read "fuck Cubism", White’s designs for FOE break down the figure into separate elements intersecting at unnatural angles: Sarge’s cap shows the top and side of the brim from one angle simultaneously, his lower face fades into a cascading beard of scales and his moustache has slid up to land just below his gazing eyeball. White has packed a lot of things into these pieces, but simple entertainment is not among them.

If Wayne White had to be reduced to one primary aspect of his art, it would be more accurate to portray him not as Wayne White, the comedic entertainer, but as Wayne White, the illusionist poet. The most impressive thing White does as an artist is excel at that fundamental quality of visual art making: seeing one’s ideas made tangible. The thrift store lithographs have become an appropriate vehicle for whatever linguistic observations he might have. They are a preexisting space that he can fill to draw us in—as are the gallery spaces he fills with his giant cardboard installations.

I can only wonder how the relationship of the Wayne White and his work will ultimately reconcile. As his fan base continues to grow, with the documentary being the most powerful introduction to him, will the number of dick jokes and “fuck you” signs increase to meet the demand? The word paintings in this exhibition represent a return to the form after a hiatus; perhaps that is why they are all completely legible, as opposed to stretching letters beyond recognition or having them break the picture plane as he has often done in the past. Or is it more in the installations that White’s future big artistic developments seem to lie? He has hinted at a public project that is so obvious it is brilliant: an installation that would actually place text within the real-world Chattanooga landscape, in his home state of Tennessee. It almost doesn’t matter what the content ends up being, since there has never been an installation opportunity White hasn’t completely made his own; I expect this would be doubly so. It promises to be an exciting and ambitious continuation of his work, and when the time comes, I will definitely be making Tennessean travel plans to view it.

1 Wayne White Q&A with Todd Oldnam and Miriam Katz at SVA Theater 9/10/14

http://joshualinergallery.com/exhibitions/white_invisible_ruler_september_11_2014/press/

2 ibid

JF Lynch was born in Boston in 1980. He received his BFA in illustration from the Art Institute of Boston in 2002 and his MFA in Painting and Drawing from Pratt Institute in 2011. He is the Visual Arts Editor for apt Literary Journal and, along with Paul M. Nicholson, curates the pop-up gallery Botanic in Bushwick. JF currently lives and works in Brooklyn, NY with his with wife, illustrator Robin E. Mork.

Shackface Mooneye

2014

Cardboard, wood, acrylic

48 x 36 x 48 inches

You can follow Wayne White on Instagram for the "free eyeball rides"

http://instagram.com/waynewhiteart

Invisible Ruler

September 11- October 11 2014

joshualinergallery.com/exhibitions/white_invisible_ruler_september_11_2014/

Joshua Liner Gallery

540 West 28th St

New York, NY 10001

From the Press Release:

Wayne White has had an extensive career as an artist and art director. Many of his enthusiastic admirers know his work from “Pee-wee’s Playhouse,” of which he has won three Emmy Awards for production design. White is also noted for his music videos for Peter Gabriel and The Smashing Pumpkins. More recently, White’s journey from young art student to his current studio practice was documented in the film Beauty is Embarrassing.

© 2014 Scott Robinson

Disclaimer: All views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors, owner, advertisers, other writers or anyone else associated with PAINTING IS DEAD.