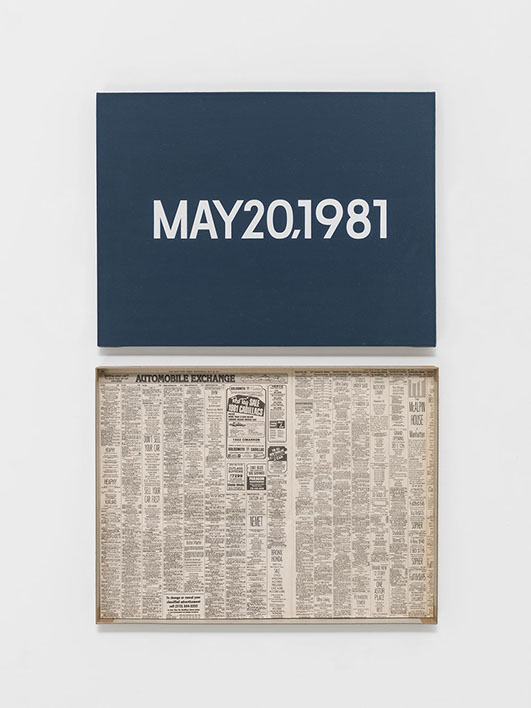

On Kawara, MAY 20, 1981

“Wednesday.” New York, From Today, 1966–2013

Acrylic on canvas, 18 x 24 inches (45.7 x 61 cm)

Pictured with artist-made cardboard storage boxes, 24 5/8 x 18 5/8 x 2 inches (62.5 x 47.3 x 5 cm)

Private collection

Photo: Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

Eternity Observed: On Kawara Silence

When writing about the oeuvre of On Kawara, one is immediately wary of words, or rather, there is a distinct feeling that more words need not be added to a body of work already made up of letters and numbers. I am reminded of an interview with musician Dan Bejar (of the bands Destroyer and the New Pornographers) that I find myself coming back to quite often when thinking about perception of art. The interviewer asks him about language and lyrics in relation to his live shows. Bejar says there are certain bands who put on shows at which “people go to church”, bands that somehow have a spiritual dimension to their concerts, which is different from just putting on a great show.1 The same can be said of art exhibitions, and stepping into the Guggenheim, Silence immediately struck me as a show at which one would “go to church”. There is something reverent about its mathematics placed in the Fibbonacci-ing Guggenheim, sublime in the same way collected Mark Rothko or Barnett Newman paintings are, where the viewer feels somehow disembodied. Consciousness of self is losable and only silence remains, which is no doubt the spirit in which the show was titled.

Kawara’s most welll-known work, the Today series, uses a technique that may feel familiar to the sign-painterly techniques of Jasper Johns or Robert Indiana, but is conceptually opposite. He is graphic but somber, inward facing. Though news media and landmarks occasionally appear in his work (specifically in the postcards and boxes created for the date paintings), his relation to these elements is diametrically opposed to that of Pop Art’s. He presents these artifacts as a sober documentarian, celebrity and advertising have no privileged place in his work. If they happen to appear, it is incidental, the noise of modern experience, absorbed rather than amplified by Kawara’s austerity. In presenting massive amounts of information, Kawara still leaves out the titillating specifics we crave (which Pop Art was so good at providing). His data is mathematical but impersonal, only a skeletal framework.

Installation view: On Kawara—Silence Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 6 to May 3, 2015.

Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

I clearly remember my first encounter with a Kawara date painting some years ago. I was unfamiliar with the series and assumed the painting, presented outside of the context of the series, was a one-off work. Even on its own, it held incredible mystery for me: what did happen on December 28, 1971 that justified memorializing it on a canvas? It was funereal, but the painting set off a chain of lively mental speculation—that single date rendered in white on an almost black background could be imagined as either the most eventful or mundane of days.

From that day on, I became an admirer of Kawara, someone who did so cleanly and completely what I have an incredibly difficult time doing in my own practice: focusing on one thing at the expense and exclusion of all other possibilities. This Zen-like commitment is evident as the Kawara retrospective unfolds along the Guggenheim’s spiral—as the maxim goes, “a little and a little makes a lot.”

In Ben Davis’ Artnet review of Silence, he casts Kawara as a prescient political artist, spinning “art out of existential metadata” even before we became conscious of the reaches of the digital surveillance state.2 It’s tempting to take Kawara’s work as particularly relevant post-Snowden’s NSA revelations, seeing Kawara as a collector of personal information and habits. But it also somehow cheapens it. Approaching Silence in this way is a kind of presentism, a nunc pro tunc fallacy. The self is not tracked in the names, dates, times and routes he presents so much as it is lost, our information on Kawara fills out very little of his actual personal life. What causes Kawara’s silence to resonate is its universality, its commonness throughout history, not its personalness. Instead, I would argue, Kawara serves a different function—the priestly one of ritualized existence.

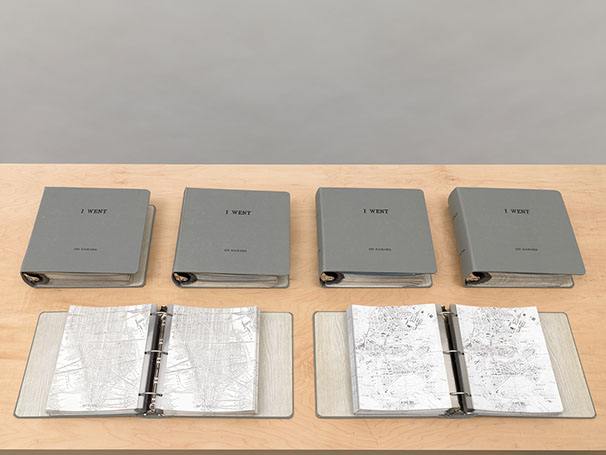

On Kawara, I Went, 1968–79

Clothbound loose-leaf binders with plastic sleeves and inserted printed matter

Twenty-four volumes, 11 1/2 x 11 13/4 x 3 inches (29.2 x 29.8 x 7.6 cm) each

Sleeve size: 11 1/16 x 8 5/8 inches (28.1 x 21.9 cm)

Inserts: Ink on photocopy, 11 x 8 inches (27.9 x 20.3 cm) each

Collection of the artist

Kawara does not document himself so much as he documents the commencement, presence and closing of another sidereal day—the earth’s continued rotation and all that takes place therein. He is an observer, and while there is metadata present, it is not his own, so much as it is the calendar’s and the clock’s. Even in documenting his paths through cities (the I Went series) or his roster of daily meetings (the I Met series), the subject is not Kawara himself, but rather the performance of utilizing the time-space that the given 24 hour period provides. They serve as ways of tracking the vantage points from which he observed the passing days. Kawara’s paintings are performative as well, either completed within the date they portray, or destroyed. He utilizes the pieces as stretcher bars with which he extends the canvases of endlessly repeating 24 hour increments. In Kawara’s work nothing is done hastily,but everything is executed mindful of passing time.

It’s the invisible performative element of Kawara’s work that comes through most strongly in the Guggenheim’s retrospective. The readings of One Million Years demonstrate this most apparently, but every inclusion, from the paintings to the postcards, reveal a Kawara who was committed to anonymity.

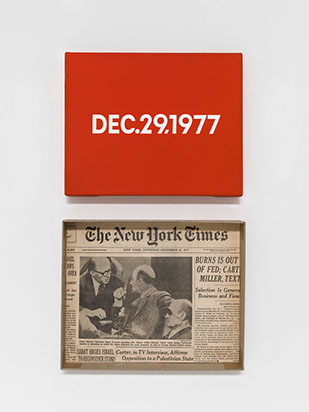

On Kawara, DEC. 29, 1977

“Thursday.”, New York, From Today, 1966–2013

Acrylic on canvas, 8 x 10 inches (20.3 x 25.4 cm)

Pictured with artist-made cardboard storage boxes,

10 1/2 x 10 3/4 x 2 inches (26.8 x 27.2 x 5 cm)

Private collection

Photo: Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

The boxes made to contain each painting in the Today series serve to transfer Kawara’s work from the personal to the universal. Crafted alongside the paintings each day, the boxes are lined with a newspaper, recording the day’s events. It is both his and our existence in the day that is being recorded—a verification that June 16, 1966, Oct. 31, 1978, or Mar. 5, 2000 took place as observed by Kawara. Here there is nothing to suggest surveillance, but instead Kawara stands as a high-priestly figure, doing what must be done for all of humanity. Through the meditational act of hand-rendering the numbers in a seemingly mechanical way, he removes personality and specificity. Our understanding of metadata today is preeminently intimate. It does not record the simple fact that you exist so much as it records the peculiarities and details of such an existence. This is just the opposite, it is existence with the removal of the self, it is meditation.

Kawara reminds us that conceptualism’s potential for timelessness is what makes

it so attractive. Strong conceptual work is seemingly free of any style or affectation, and is an appeal to mathematics and systems as eternal truths, and therefore “un-outdatable”. Even language is broken down into systems, building blocks, if the rules set are compelling enough, then it is enough for the artist to fulfill them, even if it is in a rote way. Peculiarly, rote becomes sublime,and the incremental documentation of time somehow creates timelessness, that acute awareness of the specious present, sometimes sliding and sometimes slogging along, converting the future into the past. The timelessness of Kawara’s work made his recent passing all the more poignant—who among us now observes the days with the keen attention that he did? Silence presents a body of work that was always created in funeral dress but which, fittingly, outlives both the day it was created for and the artist it was created by. Upon exiting the Guggenheim, it was not the dates, names, figures or phrases of the exhibition that rang in my head, but a passage from Hippocrates, uttered in a year that was no doubt recorded somewhere in Kawara’s One Million Years (Past) books—ars longa, vita brevis. Art is long, life is short.

1 Destroyer By Matt LeMay, Pitchfork, June 12, 2006 http://pitchfork.com/features/interviews/6357-destroyer/

2 What On Kawara's Analog Wisdom at the Guggenheim Has to Offer a Digital World By Ben Davis, Artnet News, February 6, 2015 https://news.artnet.com/art-world/what-on-kawaras-analog-wisdom-at-the-guggenheim-has-to-offer-a-digital-world-246126

Installation view: On Kawara—Silence Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 6 to May 3, 2015.

Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

On Kawara: Silence

February 6 to May 3, 2015

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

1071 Fifth Avenue

(at 89th Street)

New York, NY 10128-0173

Hours

Saturday - Thursday: 10:30am-5:30pm

Friday: 10:30am-8:00pm

Disclaimer: All views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors, owner, advertisers, other writers or anyone else associated with PAINTING IS DEAD.