Stacks of paintings in the studio of Clare Grill

Photo: Scott Robinson 2014

Matt Kleberg with Clare Grill

September 5th, 2014

On the occasion of two upcoming exhibitions (September 5th at Fred Giampietro in New Haven, CT and October 18th at Diane Rosenstein in Los Angeles, CA), I visited Clare Grill in her studio, which was full of new paintings. We talked over the hum of a fan and drank beers while discussing a variety of topics ranging from working on larger-scale paintings, to embroidery, to New Casualism.

-Matt Kleberg

Matt Kleberg (left) and Clare Grill (right) in the studio of Clare Grill

Photo: Scott Robinson 2014

Matt Kleberg: It looks like you have been busy this summer.

Clare Grill: I have a couple shows coming up and I’m making some big paintings. I’m pretty psyched about it actually. It’s been a pretty great transition. I’m excited about these.

MK: Has the process changed at all with the larger scale?

CG: I make the little ones in my lap. I usually hold them really close because I like to see the raking light. In fact, usually I don’t have lights on. I paint in the morning and there’s not a lot of light, but I can see the surface really well. I also like being really close so I can’t see exactly what is happening- I like to get inside the painting. Now, working large, it’s naturally that way because I am physically smaller than the paintings. I can’t comprehend the whole. So far I’ve been making the large ones at a table so I can move around them the whole time. And then at the end of the day, or when it gets too dark, I’ll put them on the wall and start to deal with them. It’s a give and take. It’s as much scraping away and lifting off as they are putting on, I have come to realize.

MK: Some of your paintings are more contained, like Game, where there is sort of an arena that the painting creates. But others feel more like little swatches. These larger paintings feel like an expanded view of some of the smaller ones. Like the small ones could be little parts of the bigger ones.

CG: Some do, some regard the edge more than others. I really try to keep them from feeling like pattern. You said swatch and I get what you mean. Someone recently referred to my work in light of pattern, and while that kind of imagery is very interesting to me, it’s not interesting to make a painting like that. I want those little marks to feel like maybe there’s some organization to them, but when you spend time with them you realize there really isn’t. They are flirting with the edge, vibrating in this almost-on, almost-off area. That feels important to me.

MK: Maybe instead of swatch, it’s more like mapping, like in Google maps. You can see where you are and as you zoom out and expand the view, the map keeps going.

CG: I think thats a really good observation. Thinking of where I’ve come from, I used to make more heavily image-based work where I was looking at photographs and finding little bits of them that seemed interesting, like a background or a space between two bodies instead of the person. These odd moments that—if you isolated them—created this tension over what could be happening just outside the frame. And there is this ‘slippage’, and that potential felt really full to me. Hopefully that energy is in these paintings still, even though you can’t necessarily see something you can name.

MK: Your painting Wedge seems to flirt with something recognizable without giving itself away.

CG: It’s a special painting. It was one of the very first ones I made in this current vein. A couple years ago I started looking at antique embroidery samplers. My husband turned me onto them. He’s studying early American literature and he stumbled upon them in his research and told me I should look at them. And they are just amazing things, amazing artifacts. They really get me. They give me some kind of mood, looking at them and considering what they imply about women’s history and children’s history. So I’ve been making drawings on paper that are really loosely based on these samplers. And most of these paintings I am making now are coming from little teeny parts of the drawings. Maybe the painting totally veers in a different direction, but it’s an entry point for me.

Clare Grill

Winter, 2014, oil on linen, 12" x 14"

Photo: Scott Robinson 2014

MK: Are you referring back to the (antique embroidery) samplers themselves, or just to the drawings?

CG: Just the drawings. The samplers I’m looking at, I’m not trying to tell their story. I’m not trying to translate them or transcribe them. Obviously I’m not including recognizable text. The drawings are a nod to them. They borrow from the samplers formally—the worked surface. Sometimes the paper even gets pilly. And maybe that relates to these objects as antiques that were sensitively made, but have been worn down—the hand-me-down quality. And with the paintings right now, I find that I need to step away from the original and trust that the drawing is interesting or full enough as a source, even if it’s just the glow in the background or something. Sometimes that’s where a painting will start. Then it evolves and the painting takes off.

MK: You’re talking about not wanting to simply transcribe the information from the original source, the (antique embroidery) samplers, but you title the drawings after the girls’ names.

CG: Yeah, that’s the one thing. If I can decipher the name of the girl who made it—because sometimes you can’t—then I will name the drawing after her. Again, I feel like they give me a mood.

MK: There is this sense of the knowable versus the unknowable. With bits of photos you may get a hint as to what’s going on in the rest of the frame. This thing that you could know but you can’t know. That seems to be at play with these paintings as well.

Matt Kleberg (left) and Clare Grill (right)

Photo: Scott Robinson 2014

CG: Yeah that’s great. I’m titling my show in LA Mary, Mary and after I titled it, I started to worry that it was too much—too loaded, too specific...but it’s not. It’s whatever you attach to it. It’s wide open.

MK: I’m already thinking to so many things it could be: ”Hail Mary full of grace”, “Mary, Mary quite contrary”, or the voice of someone calling to someone else off in the distance. It feels pretty open to me, while having all the specificity of a name. I mean, a name is so powerful, but when you don’t know what the name attaches to…

CG: Yeah and that too gets back to specificity. For me, specificity is pretty important. I want these to feel—even if it isn’t clear to you, or nameable, or apparent where it’s coming from—I want you to look at my paintings and feel like I care deeply about making them and that there is intentionality in what they end up looking like. You asked me about Casualism and I think that word is so complicated and debated. But these aren’t casual at all. And they aren’t slapdash at all. And they aren’t accidental. They are open—I hope—and the

I want you to look at my paintings and feel like I care deeply about making them and that there is intentionality in what they end up looking like.

way they are made has become open for me. But the final thing that you see, even if it’s just lines, I want them to feel like they are my lines. Or no, it doesn’t even matter that they are my lines, but they are someone’s lines. They are needing to be a certain way. I get excited about that idea.

Anthony Huberman wrote this essay called “How to Behave Better”. In it he talks about people operating out of an ethics of either “I know” or “I don’t know”. His bookends are the boxers vs. the chess players. The boxers are like Picasso, or Matthew Barney. The chess players are Duchamp or Tino Sehgal. So people are operating out of these opposite poles, and he is calling for artists to operate out of an ethics of “I care”, “I love it” instead of “I get it”. It really resonated with me, this idea of searching over finding.

MK: That’s great.

CG: And for art-making, it is about absolutely giving a total shit about what you’re doing and what you’re making. I’m not an artist who calls my paintings my babies, but somebody once said that a painting is finished when it has a face and looks back at you, and I think that so gets at this presence that happens when you’ve made art. That can only happen when you really care deeply about what you’re doing.

From what I understand about New Casualism, it’s about everything goes. Anything and everything is valid as grounds for art-making. I think that’s interesting, and I don’t necessarily disagree with it, but I find that I need some kind of restriction in order to stimulate creativity, some kind of confines. For me right now, these drawings are that. They free me up in order to play fast and loose with painting.

MK: That is really interesting. It has a strong whiff of Guston. He talks about the paradox of feeling no freedom when something can move around anywhere in a painting. But when he can get a painting to a place where he is moving things around by inches, that is when he feels the most free—freedom in constraint, freedom in parameters.

CG: Painting the thing enough to know this one little move, rather than some big move, is going to sing. It’s going to be the key that unlocks the whole.

MK: That’s a great word, sing.

CG: Yeah, I find I am using that word a lot, especially in regards to installing these paintings. As you see, they are various—all different sizes, all different linens. They are made in different ways. Sometimes it feels really chaotic in here—cacophonous, jarring, discordant—and I get anxious before hanging a show. It’s hard to see it coming together and it feels like too much, but I have found that there is a right installation of the work. And my job is to move things around until I find it. For example, at Soloway when we first hung the show and it felt cold, minimal, modern. It felt like it wasn’t my work. So we came back the next day and redid it and they sung. I love that about installing; it’s like making a painting writ large, moving little pieces around.

Clare Grill

Wale, 2014, oil on linen, 20"x 24"

Photo: Scott Robinson 2014

MK: What about (your show at) Reserve Ames (Gallery), where it wasn’t just the work talking to the other work, but in an unconventional space that adds to the conversation?

CG: That was nuts. I had never been there. I brought six goddamn tiny paintings—such a gamble. I literally brought the work that fit in my suitcase.

MK: Had they sent you pictures?

CG: I saw three iPhone snapshots and even then I didn’t really bother to imagine the space. We were just winging it and it was crazy. When I got there, it was obvious where everything should go. I mean, there was writing on the wall that mirrored marks on one of the paintings. There was this blue stainy thing on this one piece of wood that was exactly the shape and color of a part of another painting—weird things like that. It freaked me out. Also—and this is so cheesy—but the back half of that space was a garage where their neighbor was just storing a bunch of old farming shit, like old scraps of wood and chicken wire, you know, garbage. You could see back into that space and I thought it would be interesting to activate it, to do something intentional with it. I was rooting around back there and found a stack of notecards on an old furnace. They were flashcards written in pencil for a geology test—as far as I could tell—and the card I picked up was about crystallization of mineral or rock or whatever. And the painting I wanted to hang back there was titled Crystal. I mean all kinds of freaky things happened with that show—and in three hours too.

MK: So this flashcard in its discarded state was part of someone’s past, evidence of some narrative, but you can’t attach it to the whole. It’s just a little chip of a whole. It isn’t totally different than these (antique embroidery) samplers, which are also echos of the past. What is it about time, age, or memory that compels you?

CG: I don’t know if I know. I think there’s something about the past that is intriguing to me in that you can never know entirely. There is a blurriness to memories and to someone else’s past. You can hear about it, but it is altered. It is weathered. And that kind of mystery, that in-betweenness, feels to me like a really full place to operate out of, as an artist. There is some sort of rudder, something tethering you, but you can never really know.

There is a blurriness to memories and to someone else’s past. You can hear about it, but it is altered. It is weathered. And that kind of mystery, that in-betweenness, feels to me like a really full place to operate out of, as an artist.

MK: You said the past and this weathered feeling leave a rich landscape to explore. I feel like it could also be tricky too, with nostalgia and sentimentality potentially right around the corner when one deals with the past.

CG: Yeah, I prefer to use the words melancholy and homesick.

MK: We’re not talking about the Golden Oldies here.

CG: Right. But I don’t even know that nostalgia and sentimental are bad words in art-making. I mean, I don’t think they should be. I think whatever gets you, whatever place you need to go to be moved to make something is valid. That kind of heart-achey place of thinking about the past, and family and personal things is enough for me to go from. I think maybe that’s what makes a mood. I keep using that word, moody, and it’s so abstract, but i don’t know how else to say it.

MK: Would you say the earlier more photo-based paintings have more personal narrative built into them?

CG: Maybe more directly, but I like to think these recent paintings are just as personal. I have stripped away, for the time being, recognizable images, and trusted that touch and texture and the dryness or waxiness or dustiness of color can communicate that kind of information just as well in a ‘sideways’ way, or an out-of-focus way, but in a potent way.

MK: So the materiality is translated into the feeling of memory.

Matt Kleberg (left) and Clare Grill (right)

Photo: Scott Robinson 2014

CG: I like that. The feeling of memory… There’s this painting I made called Glove that came from a teeny little shape in one of the sampler drawings. All the little marks in the larger painting came from super close attention paid to the hairy little brush marks on the drawing. So I am digging really deeply into what’s there and trying to reactivate it or bring it back to life.

MK: Do you think of yourself as an abstract artist?

CG: I always hate those designations. I suppose it’s partly because I don’t think of painting that way. I think of painting as painting. I’m not denying that those things are real designations, but to choose to be one or the other feels like too much to handle. I just want to make paintings. A couple years ago I heard a lecture from the 1940’s with the artist Richard Pousette-Dart. The students were asking him what was better, representation or abstraction? And he was fighting them tooth and nail all night long about it, refusing to take a side. He said “To paint a flower is to paint a lie. To paint a painting is to paint a flower.” For me it was like DING DING DING! It changed everything. It made total sense, unlocked the door or something. I love that. It is about painting, not about any other story or any other thing you can name. So I don’t know if I’m an abstract artist. I am a painter.

MK: Black and white categories aren’t helpful.

CG: Right. That quote is about openness and giving yourself permission to play chess or box. It is about everything.

Titling gets at the same thing. The titles of the samplers have a logic to them. But for everything else, I keep a list on my phone and in notebooks of words I come across—usually in novels or poetry, just words that I like. So when I have a bunch of paintings and it’s time to title them, I will sit and attach titles to them. It is an intuitive connection and I’m careful not to close the painting. I heard some quote, I think it was Paul Valery, “Poems fall apart when they vanish into meaning’” or something to that effect. When you say too much, if you show too much, you destroy it. I think that’s fair. And I operate from a similar cautious place when titling—and when making, really.

Clare Grill

Swan, 2014, oil on linen, 15" x 16"

Photo: Scott Robinson 2014

MK: The poem could die or the painting could die if you kill the mystery.

CG: Yeah, if you know what you’re doing beforehand in art-making, why are you doing it? Then you’re doing something else—design perhaps. I don’t want to dismiss it entirely. But personally, there’s no magic there for me.

MK: That reminds me of Guston again.

CG: Yeah I have been reading the collected writings, and almost every page is dogeared. The other thing he talks about that kills me is this idea of compressing the amount of time between thinking and doing. I forget how he says it, but basically you are not thinking, you’re just doing. It made me think of this other lecture I heard by Agnes Martin talking about how intellect has no place in the studio. It sounds flippant, or corny, but that’s the place I need to get to when I’m painting.

MK: Guston was trying to cut out any sort of pause between impulse, hand, and canvas.

CG: He tried to find the place where the image hovers, where it is not completely fixed. It’s on the brink, he says, as if it’s always been there yet only almost there.

MK: Right, that moment of pause where it could move off somewhere else the next moment.

CG: Yeah, I love that. That’s the tension I’m talking about—that vibrating space. Even if you’re dealing with line or geometric predetermined forms, I think you can try for that kind of just offness that opens up all these possibilities.

MK: Guston talks about the occasional one-off painting, but mostly he talks of paintings scraped and painted-over—paintings that have lived through something. I get a sense that you value that, that the paintings have undergone something.

CG: Yeah, I would way sooner rework and scrape-off or sand-off and find new life in the painting. I don’t have the painting in mind. I have a fleeting little, you know, impulse in mind, a shape or a thing thats good enough to start it, but I don’t have a plan in that way. I know for myself that the working through of it… Maybe that’s the point of the history, to enrich the final thing.

When I was working on that painting of my mother as a child, years ago, she was flesh colored. She was all painted with blonde hair and everything. And my impulse was to make her blush, to give her this blushing cheek because I thought that the mood, the feeling of that image made me think of a young girl who’s uncomfortable. In the picture, she was in the background and looked kind of sad—and I don’t know if she even was sad—but it was a sad sort of glimpse of her, and I had been thinking of all these rites of passage and growing up and I thought she should be blushing or ashamed or nervous or flushed or physically uncomfortable. So I painted it that way and I showed my husband and he was like “It’s such an obvious move. It’s already there. All those things, the way she’s there and her posture, the weight of her… It’s already there.” And I was like, “ah fuck, what should I do?” And I painted it over, just pushing her into the background, painting her out. And then I thought “oh wow, this is a painting now. This just went into another place.”

Matt Kleberg and Clare Grill discuss portrait of Clare's mother.

Photo: Scott Robinson 2014

MK: Right.

CG: It was one of the first times where I felt like I had given myself permission, or had gotten permission, to trust it to trust that this is enough. Yeah, you’re not telling the whole story, but there’s enough there to give you the feeling of the whole story, and that residue is what’s really potent and full.

MK: Is that a question that comes up in these paintings, ‘enough’? Is this enough or is that enough?

CG: When I’m making them? Yeah, definitely.

MK: Because that ties into the question of how you know when one of these is done.

Stack of unfinished paintings in the studio of Clare Grill

Photo: Scott Robinson 2014

CG: I mean, it’s the thing I mentioned earlier when a painting looks back at you, when it has a face. When it has a presence, it says “I exist, so don’t mess with me.” I know that sounds confrontational and I don’t mean it to be, but that’s when. When I believe it or when it doesn’t feel toxic in the space any more… Because until they are finished, they do feel jarring and irritating. These over here are all unfinished. And it could be a really tiny move or a total face-lift that is needed. I really work from that place, that felt place. I am just trying to situate these paintings in that buzzing, in-between space where they are just paintings. It sounds dumb, but that is what it is. They are just paintings.

MK: Can you talk about artists you are looking at?

CG: People I love? There was a time when I really had my face in books studying my heros. I used to devour Mama Anderson and Peter Doig books. I loved them. I felt like I had never really looked deeply at art books before that. And those were people looking at (working from) photos and I was like “oh, you can do that?” I didn’t know. It blew my mind. And then, you know, you get to a point where you start growing your own muscles and realizing “maybe I would do that differently” and that’s such a great feeling.

MK: You start critiquing your heros.

CG: Yes! And then you close the book and go on your way. But as for contemporaries, I love Michael Berryhill’s paintings. I love talking to him about painting. I feel like he’s doing what I’m aspiring to do—making Paintings with a capital P. Patricia Trieb is a great painter. Scott Olsen, amazing abstract paintings. Nat Meade for sure… Norbert Schwontkowski was my jam, God rest his soul. The way he works up those filthy sparkly surfaces… I like Matt Phillips. He feels like a kindred spirit. I will go to every one of his openings and geek out about his paintings. They are super sensitive, dry, gorgeous. He will make a painting for a year.

MK: Can you talk about your experience at Skowhegan?

CG: I went in 2011. I loved it so much, all of it. Some people have different experiences of it, but for me it changed everything. I had applied for years and when I finally got to go I was ready. I had just done a show in New York and felt confident. But I was also really ready to be pushed. I had lots of head space and was eager to absorb something—whatever it was. It was such a gift. I felt really spoiled. All I had to worry about for nine weeks was eating.

MK: It sounds pretty idyllic. Well, is there anything else? If you could be a tree what would you be? Just kidding...

CG: A Christmas tree! (laugh)

MK: Favorite color!

CG: Blue!

Clare Grill is an artist living and working in Queens, NY.

Matt Kleberg is an artist living and working in Brooklyn. He is currently pursuing his MFA in Painting at Pratt Institute.

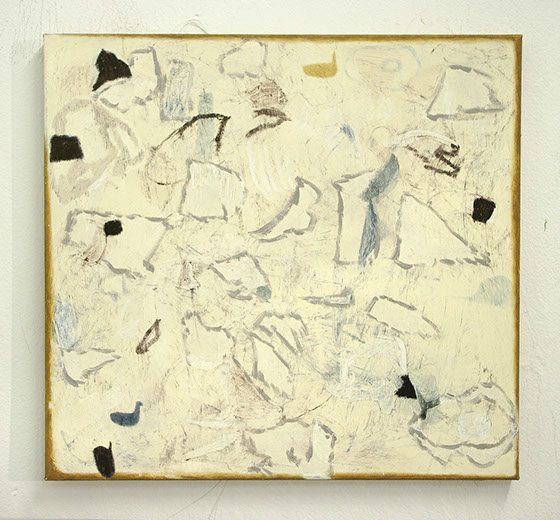

Clare Grill

Idle, 2013, oil on linen, 33" x 40"

Photo: Scott Robinson 2014

Disclaimer: All views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors, owner, advertisers, other writers or anyone else associated with PAINTING IS DEAD.